Isolation or Integration? North Korea’s Diplomatic Network

Commentary | November 13, 2023

Antoine Bondaz

Director of Korea Program on Security and Diplomacy, FRS

Antoine Bondaz, the Director of Korea Program on Security and Diplomacy at the Foundation for Strategic Research (FRS), explores the state of North Korea’s diplomatic relations with the international community. The author points out that despite severing relations with numerous countries due to international sanctions, North Korea maintains diplomatic exchanges with a significant number of countries, rendering its nickname “hermit country” outdated. Highlighting that North Korea has been growingly prioritizing its relations with like-minded regimes facing international sanctions and pressure like itself, Bondaz claims that North Korea will continue “selective engagement” with specific partners in Africa, the Middle East, and South Asia, while partially “decoupling” from hostile countries. This commentary was co-published by the FRS and Global NK.

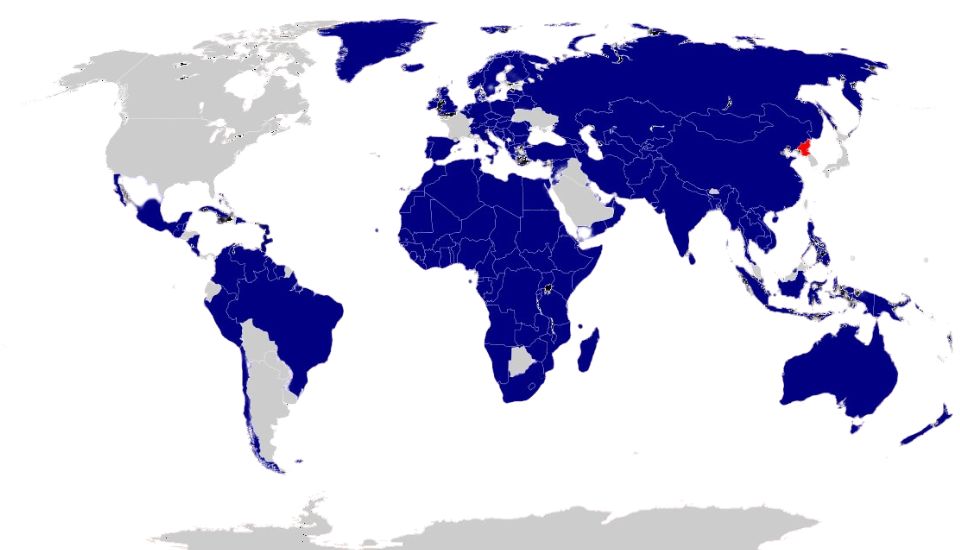

The recent meeting between Kim Jong Un and Vladimir Putin presents an opportunity to assess the diplomatic relations of the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK). North Korea is often incorrectly depicted as isolated on the international stage. However, the country maintains relations with a significant number of countries and possesses a substantial diplomatic network, dispelling the stereotype of a “hermit country”.

Despite being subject to a range of international sanctions, both those imposed by the United Nations Security Council and unilateral sanctions by specific states like the United States, South Korea, and groups of states such as the European Union, these measures do not inherently hinder the diplomatic relations that North Korea can establish with its partners, even though there has been mounting pressure since the mid-2010s.

Since 1991, the DPRK has held a seat at the UN and is a member of numerous international organizations. Most notably, it maintains diplomatic relations with approximately 160 states, which is over 80 percent of UN member states. Despite its limited financial resources, the country keeps a diplomatic network comprising dozens of embassies worldwide on all continents, with several dozen countries having an embassy in Pyongyang.

A gradual and continuous expansion of diplomatic relations

Upon its establishment in September 1948, the DPRK sought to establish diplomatic relations with countries in the communist bloc, including Albania, Bulgaria, Poland, Romania, the USSR, Mongolia, and others. Diplomatic ties with Beijing date back to 1949, the year the People’s Republic of China was founded. Some of these countries played pivotal roles in the Korean War (1950-1953) and in the reconstruction of the country in the 1950s.

Starting in 1960 with the establishment of diplomatic relations with Cuba, the DPRK diversified its partners, particularly with newly independent countries in Africa and Asia, including Egypt (1963), Cambodia and Indonesia (1964), Syria (1966), Chad, and the Central African Republic (1969). In a decade, North Korea tripled the number of its diplomatic relations, significantly expanding its international cooperation network.

The 1970s marked a significant acceleration in Pyongyang’s diplomatic efforts. Between 1972 and 1975, no fewer than 52 countries established diplomatic relations with the DPRK. While many were in Africa, such as Senegal (1972) and Angola (1975), and in Asia, like India (1973) and Thailand (1975), European countries outside of NATO also recognized the Pyongyang regime. The five Nordic countries acknowledged the regime in 1973, followed by Austria, Switzerland, and Portugal in 1974.

In parallel, North Korea started joining international organizations, including UNCTAD and WHO in 1973, IAEA and UNESCO in 1974, FAO and ICAO in 1977, and UNDP in 1979. This transformed North Korea from a pariah state to an integral part of international society.

The 1980s witnessed a relative slowdown in North Korea’s diplomatic network expansion, marked by incidents like the attack on the South Korean presidential delegation to Burma in 1983 and the bombing of an airliner in 1987. In that decade, the country established diplomatic relations with dozens of countries, including Mexico in 1980 and Lebanon in 1981. North Korea also joined more international organizations, including UNICEF in 1985 and the WFP in 1986.

In 1991, North Korea, along with South Korea, joined the UN. The country continued to establish diplomatic relations, particularly with African countries like Djibouti in 1993 and South Africa in 1998, as well as Caribbean countries such as the Bahamas and Saint Kitts and Nevis in 1991. Pyongyang also recognized the 15 new republics created by the collapse of the USSR (between 1991 and 1994), and the countries of Central and Eastern Europe formed by the division of Czechoslovakia and Yugoslavia.

At the turn of the millennium, South Korea’s engagement policy with North Korea, known as President Kim Dae-jung’s Sunshine Policy, led Western European countries, hoping for positive changes in the regime, to establish diplomatic relations with the DPRK. Italy was the first in 2000, followed by the United Kingdom and Belgium in 2001. Except for France and Estonia, all current EU member states have established diplomatic relations with Pyongyang. This also applies to Brazil, Canada, and Turkey (2001).

On a more anecdotal note, the United Arab Emirates formally recognized the DPRK in 2007, and South Sudan was the last to do so in 2011, following the partition of Sudan. Although France lacks diplomatic relations with the DPRK, it opened a cooperation office in Pyongyang in 2010. Additionally, there is a general DPRK delegation in Paris.

While nearly 80 percent of UN members have diplomatic relations with North Korea, major countries like the United States, Japan, and South Korea have never established such relations. This remains a subject of numerous negotiations as North Korea seeks to normalize its relations and gain formal recognition.

In the absence of diplomatic relations, Washington and Tokyo also refuse to open a liaison office in North Korea, unlike Seoul, which, following the Panmunjom agreement in 2018, opened an office in Kaesong, on North Korean territory. However, this office was destroyed by North Korea in 2020.

The nuclear crisis and its impact on diplomatic exchanges

Although North Korea’s first nuclear test in 2006 did not result in sanctions specifically targeting its diplomatic network, the situation changed significantly in 2016 and 2017 with the last three nuclear tests. United Nations Security Council Resolution 2321 (2016) called for “all Member States to reduce the number of staff at DPRK diplomatic missions and consular posts” for the first time.

While Resolution 2397 (2017), the last resolution adopted independently by the United Nations Security Council, reiterated that these resolutions “shall in no way impede the activities of diplomatic or consular missions in the DPRK pursuant to the Vienna Conventions on Diplomatic and Consular Relations”, the United States urged its partners and allies to exert pressure on the DPRK by targeting its diplomatic network.

During a tour of Latin America in 2017, Vice-President Pence called for the diplomatic isolation of the Kim regime and the severing of all diplomatic and commercial ties with North Korea. Several countries took action. Spain, Kuwait, Peru, and Mexico expelled the North Korean ambassador. Thailand, Singapore, and the Philippines discontinued all economic relations. Portugal went even further by ending its diplomatic relations with the DPRK, which had endured for almost fifty years.

Some countries had already terminated diplomatic relations with the DPRK. For example, Botswana did so in 2014 following the publication of a UN report on human rights violations in North Korea, with the support of South Korea at the time. In 2021, it was the DPRK that terminated its diplomatic relations with Malaysia following the conclusion of the trial in Kuala Lumpur concerning the assassination of the half-brother of Pyongyang’s leader, Kim Jong Nam.

More recently, in July 2022, Ukraine severed diplomatic relations with the DPRK after Pyongyang recognized the self-proclaimed independence of the Ukrainian regions of Donetsk and Luhansk.

Despite international pressure and the mentioned cases, North Korea still maintains a substantial diplomatic network, with official relations established with more than 160 countries and around fifty embassies or permanent representations in New York and Geneva. Before the Covid-19 pandemic, approximately thirty countries had an embassy or representative office in Pyongyang.

What are the short-term prospects?

The ongoing deterioration in relations between North Korea and numerous countries, not only in the West, is leading the regime to prioritize relations with other states that are also under sanctions or facing international pressure. Syrian President Bashar al-Assad announced in 2018 his intention to visit North Korea, and the Burmese junta appointed a non-resident ambassador for the DPRK in 2023, with the ambassador in China assuming this role.

Conversely, North Korea appointed a non-resident ambassador to Burkina Faso in March 2023, with the ambassador to Senegal fulfilling this role. The West African country, which has experienced a coup d’état, even declared its intention to import arms from North Korea, which would constitute a violation of Security Council resolutions since 2006.

In the context of the Israel-Hamas conflict, North Korea openly criticized the Jewish state, with which it has no diplomatic relations. In contrast, Pyongyang has maintained relations with the Palestine Liberation Organization since 1966 and since 1988 has supported the creation of a Palestinian state encompassing Israel within its current borders, with the exception of the Golan.

More broadly, the current reopening of North Korea after four years of closure due to the Covid-19 pandemic presents an opportunity for the country to resume its international cooperation and deepen these relations. However, one likely scenario is that it will do so selectively, engaging with specific partners in Africa, the Middle East, and Southeast Asia, while partially decoupling from countries unwilling to make any concessions to North Korea.

Moreover, in a remarkable turn of events, trilateral collaboration between Seoul, Tokyo, and Washington achieved unprecedented strides in the summer. This culminated in a historic summit of heads of state and government in the United States, where a momentous joint declaration titled “The Spirit of Camp David” was released. However, the question now looms whether a parallel trilateral partnership will materialize between Pyongyang, Moscow, and Beijing. This kind of cooperation was conspicuously absent during the Cold War era due to the Sino-Soviet split in the 1960s. Notably, to this day, not a single trilateral summit, not even among foreign ministers, has taken place.■

To find out more:

ARMSTRONG Charles K., Tyranny of the weak: North Korea and the world, 1950–1992, Cornell University Press, 2013.

BALLBACH Eric, “North Korea’s Engagement in International Institutions: The Case of the ASEAN Regional Forum”, International Journal of Korean Unification Studies, 2017, Vol. 26, n° 2.

YOUNG Benjamin, “Cultural Diplomacy with North Korean Characteristics: Pyongyang’s Exportation of the Mass Games to the Third World, 1972–1996”, The International History Review, 2019.

YOUNG Benjamin R., Guns, Guerillas, and the Great Leader: North Korea and the Third World, Stanford University Press, 2021.

This article was co-published by FRS and Global NK.

■ Antoine Bondaz, Ph.D., is Director of the Korea Program on Security and Diplomacy at the Paris-based Foundation for Strategic Research (FRS).

■ Typeset by Jisoo Park, Research Associate

For inquiries: 02 2277 1683 (ext. 208) | jspark@eai.or.kr

Security and External Relations

From Unification to Peaceful Coexistence

Bumsoo Kim | October 31, 2023

Analyzing the Russia-DPRK Summit and Its Outcome

Yoonhee Kang | October 16, 2023

Dealing with North Korea Beyond the Korean Peninsula: Japan’s Perspective on a New Indo-Pacific Geopolitical Trend

Kei Koga | September 27, 2023

LIST