■ See Korean Version on EAI Website

I. North Korea’s “New Line of Bolstering Up the Nuclear Force”

In early 2025, North Korea persistently reiterated its “new line of bolstering up the nuclear force.” Beginning with a statement by the Director-General of the Department of Foreign Policy at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs on January 17, 2025, Pyongyang escalated its criticism of ROK-U.S. joint military exercises at the outset of the year (KCNA Watch, 17 Jan 2025). Following remarks by Chairman Kim Jong Un, the regime repeatedly reaffirmed its intention to advance nuclear-force modernization. Because North Korea has long pursued enhanced nuclear capabilities, the declaration of a “new” line naturally raises questions about the nature and implications of this shift.

On February 8, during a visit to the Ministry of National Defense commemorating the 77th anniversary of the founding of the Korean People’s Army, Kim Jong Un reaffirmed that the nation would “rapidly” implement a series of new plans to bolster “all deterrence including nuclear forces.” He asserted that expanding ROK-U.S. joint drills and trilateral security cooperation with Japan, led by the United States, was fomenting military imbalance in Northeast Asia and “raising a grave challenge to the security environment of our state.” This statement thus signaled an intention to adopt military countermeasures (Reuters, 8 Feb 2025).

Later that month, after the USS Alexandria (SSN-757), a Los Angeles-class nuclear submarine, docked at Busan, North Korea’s Ministry of National Defense condemned the “dangerous hostile military act” that may “lead the acute military confrontation in the region around the Korean peninsula to an actual armed force conflict.” It contended that North Korean armed forces will “unhesitatingly exercise the legitimate right to punish the provokers.” (Reuters, 11 Feb 2025).

Following a joint statement on the “complete denuclearization of North Korea” issued at the ROK-U.S.-Japan foreign-ministers’ meeting in Munich, Pyongyang expressed “grave concern over the adventurist antics of the U.S., Japan, and South Korea, which incite collective confrontation and conflict on the Korean Peninsula and in the region.” It reiterated its resolve to uphold “the new line of strengthening nuclear forces declared by the head of state.” In addition, it proclaimed its intent to “continue seizing new opportunities to elevate strategic strength” and asserted that “in the structure of U.S.–DPRK confrontation, we will secure a far more advantageous position” (Seo 2025).

On 8 May, during an inspection of combined long-range artillery and missile-strike drills, Kim emphasized the need to “steadily perfect the normal combat readiness of the nuclear force.” Reports added that he underscored the necessity of “direct efforts to steadily improving the long-range precision striking capability and efficiency of weapons systems” (Reuters, 8 May 2025).

Although the precise content and method of implementation of this newly emphasized policy remain ambiguous, the initiative clearly stems from a strategic ambition to obtain superiority over both South Korea and the United States. While North Korea’s commitment to nuclear-force modernization is not new, the regime’s current intentions and trajectory merit reassessment, particularly in light of shifting global dynamics surrounding the war in Ukraine and renewed speculation about the prospects for DPRK-U.S. dialogue.

II. Historical Precedents of the “New Line”

Within North Korea’s political system, only Chairman Kim Jong Un holds the authority to proclaim a “new line.” Historically, Kim has issued such declarations multiple times, presenting them either as broad revisions of national strategy or as initiatives to advance nuclear capabilities. He frequently labels these shifts with descriptors such as “new” or “significant.” Rather than accompanying technological milestones, these announcements have tended to coincide with pivotal domestic or international political events. The following examples illustrate this pattern:

1-① March 2013: North Korea adopted the “byungjin line” as a new strategic directive (Scott 2013). In the early phase of Kim Jong Un’s rule, the regime faced intensifying international sanctions and pressure. Stabilizing the system and achieving economic growth were primary concerns. In April 2012, North Korea amended its constitution to enshrine its nuclear weapons state status, and in February 2013, it conducted its third nuclear test. Shortly thereafter, during a plenary meeting of the Workers’ Party of Korea (WPK) Central Committee, the leadership proposed and formally adopted a “new strategic line” focused on simultaneously advancing economic construction and nuclear armament.

1-② April 2018: A new strategic line was adopted that emphasized full commitment to socialist economic construction. This shift reflected favorable external developments, particularly the acceleration of inter-Korean and U.S.-DPRK dialogue. During the third plenary meeting of the Seventh Central Committee of the Workers’ Party of Korea, the regime declared its intent to concentrate all efforts on economic development. This marked a departure from the byungjin line by shifting the policy emphasis toward economic growth (National Committee on North Korea 2018).

2-① March 2014: The Ministry of Foreign Affairs stated that North Korea could consider “a new form of nuclear test” in response to the U.S.’s hostile policy (Reuters 03/30/2014). At the time, President Park Geun-hye had outlined a unification vision in the “Dresden Declaration,” which Pyongyang may have perceived as a regime threat. The regime likely intended to escalate military tensions and solidify internal unity through the specter of nuclear testing. Although an actual test did not occur until 2016, this period nonetheless witnessed a dramatic acceleration in North Korea’s nuclear capabilities.

2-② January 2020: Chairman Kim directly announced plans to develop “a new strategic weapon.” In a plenary session of the Workers’ Party of Korea, Kim proclaimed, “The world will witness a new strategic weapon to be possessed by the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea in the near future.” This statement followed the collapse of the February 2019 Hanoi Summit and was seen as a move to bolster bargaining leverage and respond to the United States’ continued hostile stance. Later that year, in October, North Korea unveiled the Hwasong-16, a new ICBM, and the Pukkuksong-4, a new SLBM, substantiating Kim’s claim (Arms Control Association 2020).

III. What Are North Korea’s Intentions and Objectives?

First, Pyongyang underscores the indispensability of nuclear force in guaranteeing regime security. North Korea regards nuclear weapons as the linchpin of the Kim regime’s survival. The Hanoi Summit revealed Pyongyang’s acute awareness of the Libyan precedent, where choosing the path of denuclearization precipitated regime collapse (Larison 2019). The war in Ukraine likely reinforced this lesson, as Ukraine’s past denuclearization failed to deter invasion (Sohn 2023). While the United States sends mixed signals by referring to itself as a “nuclear power” and calling for North Korea’s “complete denuclearization,” the regime views nuclear arms as an irreplaceable strategic asset for its survival.

Second, Pyongyang seeks to use this strategic line to consolidate internal cohesion. Facing acute economic hardship and sustained international sanctions, the regime must reinforce domestic unity to ensure political durability. Given the uncertainty surrounding a potential second Trump administration and the prospect of renewed pressure on the North, Pyongyang is likely to emphasize self-reliance and external defiance. The regime’s long-standing ideological framing of itself as the “nuclear power of the East” and embodiment of “Juche Korea” suggests that a new strategic line is inherently tied to reinforcing internal solidarity (Howell 2020).

Third, this posture constitutes a response to strengthening trilateral security cooperation among the United States, South Korea, and Japan. As strategic competition between Washington and Beijing intensifies, U.S. efforts to deepen trilateral defense cooperation are expected to continue or even accelerate under the second Trump administration. North Korea interprets the increasingly intricate joint military exercises among U.S. allies in East Asia as an existential threat, and seeks to leverage its nuclear arsenal in response.

Fourth, Pyongyang aims to increase its bargaining leverage vis-à-vis Washington. Although North Korea is drawing closer to Russia, it has not fully foreclosed the possibility of dialogue with the United States. To strengthen its position on the Korean Peninsula, Pyongyang appears intent on pursuing a more revisionist trajectory. The evolving dynamic surrounding potential ceasefire talks in Ukraine, and the respective maneuvering of Washington and Moscow, likely fuels North Korea’s strategic anxiety (AP News 6/5/2025). By adopting a more aggressive and forward-leaning posture, North Korea seeks to shape favorable conditions for future negotiations with the United States.

By proclaiming a “new line” for bolstering deterrence, North Korea can achieve multiple objectives simultaneously. First, it signals a change in national development priorities, which includes a recalibration of focus across warhead production, delivery systems, and operational doctrines. Second, it delivers a strategic message to the international community. Third, it showcases Kim Jong Un’s role as an innovative leader directing national progress, thereby reinforcing the regime’s legitimacy and stability. Fourth, it demonstrates policy flexibility, indicating that Pyongyang is capable of strategic recalibration as circumstances evolve.

|

Strategic Weapon Objectives

|

Development Progress

|

|

Development of diverse tactical nuclear weapons and production of ultra-large warheads

|

• Standardisation of 5-15 kt Hwasan-31 warheads and integration with eight delivery systems

|

• Pursuit of fission warheads or thermonuclear devices exceeding 1 Mt; orders for mass production and signs of expanded nuclear-facility capacity

|

|

Improving accuracy for targets within 15,000 km

|

• Mass production and operational deployment of the Hwasong-15 ICBM

|

• Ongoing research on the liquid-fuel Hwasong-17 and solid-fuel Hwasong-18, aiming for MIRV configurations with thermonuclear payloads and reliable re-entry technology

|

|

Prototype production of hypersonic glide-vehicle warheads

|

Test launch of the Hwasong-16Na in April 2024; development of two hypersonic vehicles (maneuvering and glide types)

|

|

Development of solid-propellant ICBMs for sea- and land-based launch

|

Lofted-trajectory test launch of the Hwasong-18 in 2023; TEL/silo and SLBM compatibility with potential MIRV payloads

|

|

Acquisition of nuclear submarines and underwater-launched strategic nuclear weapons

|

• Launch of the Kim Kun-Ok-class Hero submarine in 2023

|

• Exploration of strategic roles for the Haeil unmanned underwater nuclear attack craft, with indications of future strategic submarines capable of carrying MIRV nuclear payloads

|

IV. What’s next?

1) Evaluation of the “Five-Year Strategic Weapons Development Objectives”

Since Pyongyang has yet to specify the content of its “new” nuclear force development line, it is first necessary to evaluate its existing one. During the Eighth Party Congress on January 8, 2021, North Korea unveiled five strategic weapons development objectives that provided a clear blueprint for its nuclear ambitions. As 2025 marks the target year of the objectives, available evidence suggests that the regime has achieved a significant portion of its goals.

2) North Korea’s Strategic Trajectory

North Korea has now enshrined its nuclear-weapons status in its constitution. Drawing on Vipin Narang’s typology, some analysts contend that Pyongyang pursues a composite posture that blends assured retaliation with asymmetric escalation (Ham 2021). As the nation’s capabilities advance, however, its strategic objectives and operational priorities appear to be shifting. Anticipating the regime’s “new nuclear strategic objectives” allows inference of the underlying goals for further force enhancement.

Several developments illuminate this evolution: △Kim Jong Un’s emphasis on completing wartime readiness △the diversification of delivery platforms △the public unveiling of the Hwasan-31 warhead and the Haeil unmanned systems (Types 1 and 2) △simulated tactical-nuclear drills that include aerial detonation tests △the construction of an integrated command-and-control “nuclear trigger” (Jo 2025). Together, these trends suggest three major strategic adjustments.

First, territorial unification through limited nuclear war. By keeping the option of tactical nuclear use on the table, Pyongyang hopes to escalate conflict on its own terms and secure victory in a constrained, manageable engagement (Kim Taehyun 2024). Although some observers have argued that the “two-hostile-states doctrine,” announced in late 2023, represents a turn toward a status-quo posture (Kwon 2024; Chung 2024; Lee 2024; Kang 2024), statements during the Ninth Plenary Session of the Eighth Central Committee, as well as the 2024 policy address, reaffirm that North Korea has not abandoned its offensive ambitions. Kim plainly stated that, when internal and external conditions permit, the regime will pursue complete reunification of the Korean Peninsula.

— Toward the United States(對美): Deter, delay, and obstruct U.S. intervention and reinforcement by threatening full nuclear escalation.

|

— Toward South Korea(對南): Seek decisive military success by targeting key sites with integrated nuclear and conventional strikes.

|

Second, the emergence of “nuclear-conventional integration warfare.” This concept is designed to offset conventional weaknesses and exploit perceived gaps in the ROK-U.S. alliance (Kim Taehyun 2025). While a 2013 law described nuclear weapons as tools for deterrence, retaliation, and repulsion, the 2022 legislation openly endorsed preemptive strikes and first use in crisis scenarios.

Integration warfare envisions △mixed missile salvos △concurrent nuclear and long-range-artillery attacks △nuclear operations that incorporate cyber and electronic warfare. Such tactics are intended to achieve decisive effects across every phase of conflict: outbreak, U.S. reinforcement, strategic reversal, territorial incursions, and regime-threatening contingencies.

Third, North Korea’s nuclear force expansion goal is likely to center on acquiring an arsenal exceeding 300 warheads. Should the regime move beyond a posture of deterrence and retaliation toward one that includes preemptive use, two core objectives will shape its force structure: △optimizing the ratio between strategic and tactical nuclear weapons △ensuring the operational capability required to execute mission objectives.

To deter U.S. military intervention and wartime reinforcement, Pyongyang is expected to pursue a nuclear dyad of approximately 100 intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) and strategic nuclear submarines capable of striking the U.S. mainland and regional strategic hubs. While the reliability of these strategic systems remains uncertain, all five pillars of the strategic objectives released in 2021 are geared toward establishing precisely such credibility. It is therefore anticipated that by the end of 2025, North Korea will have achieved a substantial level of confidence in its strategic deterrent.

To secure military dominance over South Korea, the regime will likely aim to acquire around 200 tactical nuclear weapons, designed to target key military objectives such as command centers, airbases, ports, and other primary or contingency assets. Tactical nuclear systems based on the Scud series and the KN-23 (Iskander-type) are already assessed to be operational, and further deployment is expected for the Pukkuksong-1 and 2, smaller tactical SLBMs, the Haeil types 1 and 2, and the Hwasal cruise missile variants.

3) The “New Line”: Three Strategic Options

Pyongyang’s “new line of bolstering up the nuclear force” is likely to represent a progression toward limited nuclear warfare and the integration of nuclear and conventional operations. Rather than constituting a radical departure from existing policy, this new line appears to be a transitional phase following the completion of the current Five-Year Plan. In this context, three potential strategic options emerge as plausible trajectories for Pyongyang’s evolving nuclear posture.

1. Further Expansion of Strike Capabilities

This option centers on expanding the accomplishments of the current Five-Year Plan while addressing remaining technological deficiencies, with a focus on both the qualitative and quantitative enhancement of nuclear weapons. Key objectives would include the development and mass production of new solid-fuel intercontinental ballistic missiles, the large-scale manufacture of tactical nuclear weapons, and the expansion of the overall warhead inventory (Radio Free Asia, May 14, 2025). Despite North Korea’s limited foundational military capabilities, this option holds the advantage of maximizing asymmetric power through the augmentation of strike capabilities. However, it also faces a critical weakness in the persistent difficulty of establishing credible deterrence against the United States and South Korea.

2. Operational Completion of Nuclear Strike Capabilities

If North Korea considers itself to have secured existential deterrence through the Five-Year Plan, the logical next step would be to pursue operational completeness for conducting limited nuclear warfare on the Korean Peninsula. With the Hwasan-31 warhead already miniaturized, standardized, and being mass-produced, what is now required is the development of a comprehensive operational plan for the use of tactical nuclear weapons (Tertrais 2021). This would involve the following components: targeting, which encompasses detection, identification, decision-making, and execution; force planning, which aligns targets, weapon systems, delivery platforms, and operational timing; weapon systems, which include surveillance and reconnaissance assets, nuclear warheads, delivery platforms, and command-control-communication (NC3) infrastructure; and force posture, which refers to the deployment readiness and positioning of these systems. Each component must be effectively structured to ensure the full integration of tactical nuclear weapons into battlefield operations.

3. Strategic Nuclear Expansion as Leverage Against the United States

North Korea may also prioritize the expansion of strategic nuclear forces as a means of applying pressure in negotiations with the United States. Assuming that the regime already holds nuclear superiority on the Korean Peninsula, it could seek to enhance the credibility of its deterrent by securing reliable strike capabilities against the U.S. mainland through improvements to its ICBMs and SLBMs. Although the cost-benefit ratio of this approach is relatively low and existential deterrence is already assessed to be in place, North Korea may seek to leverage its deepening ties with Russia to achieve rapid technological advancement. Next-step targets under this option would likely include strategic nuclear submarines, submarine-launched ballistic missiles, and improved reentry technology for ICBMs.

Given North Korea’s current circumstances, among the three options outlined above, 2. “Operational Completion of Nuclear Strike Capabilities” appears to be the most viable course of action. The expansion of strike capabilities, while building upon the Five-Year Plan, lacks sufficient differentiation from existing frameworks and therefore offers limited utility in terms of consolidating domestic unity or conveying a distinct strategic message to external actors. Likewise, a concentrated focus on strategic nuclear forces raises concerns regarding feasibility, as it would likely entail a high degree of dependence on Russian technological support. From South Korea’s perspective, should North Korea succeed in achieving full operational readiness for the deployment and use of tactical nuclear weapons, a severe strategic imbalance would emerge on the Korean Peninsula.

V. Realizing Nuclear-Conventional Integration through the Reconnaissance-Strike Complex

Should North Korea pursue “operational completion” of its nuclear capabilities, it would likely succeed in maximizing its strategic advantages. This ambition holds significance not only at the strategic level, where it implies the possibility of preemptive nuclear strikes or multidimensional deterrence, but also at the operational level, where it would allow for a wide range of nuclear-conventional integration (CNI) combinations. These could include scenarios such as a preemptive nuclear strike followed by a conventional ground offensive, integration with asymmetric capabilities such as cyber or special operations forces, or the parallel pursuit of coercive diplomacy under the shadow of nuclear threat.

If Pyongyang does indeed intend to achieve operational completeness for the execution of nuclear-conventional integration warfare, what specific capabilities will it seek to acquire? From North Korea’s strategic vantage point, the pursuit of comprehensive superiority across all operational domains remains an unattainable objective. Consequently, the regime is expected to concentrate its efforts on finely tuned, precision-oriented strike capabilities. This focus on achieving operational completeness in nuclear strike execution appears conceptually aligned with the Russian military doctrine of the Reconnaissance-Strike Complex (разведывательно-ударный комплекс, RYK) (Lester and Bartles 2018).

The Russian version of this concept refers to real-time strategic strikes against high-value targets. In contrast, North Korea, whose conventional and intelligence-gathering capabilities remain profoundly inferior, would adapt the model to a simplified operational structure that links real-time target information with strike assets. This system would connect data collection, precision strike mechanisms, fire control centers, and tactical missile forces to deliver strikes on selected targets. It may also be integrated with long-range precision-guided munitions, including missiles and aircraft-mounted smart weapons.

North Korea is therefore likely to pursue the active development of its own version of a reconnaissance-strike complex in parallel with its nuclear-conventional integration strategy. While it currently lacks the advanced weapons systems that support the Russian model, Pyongyang may attempt to compensate for these deficiencies through technological cooperation with Moscow, focusing particularly on enhancing interoperability across functional domains. This can be seen as an effort to preserve relative superiority by maximizing asymmetry through offensive nuclear strategy, while simultaneously minimizing its vulnerabilities in strategic intelligence and warfighting sustainability.

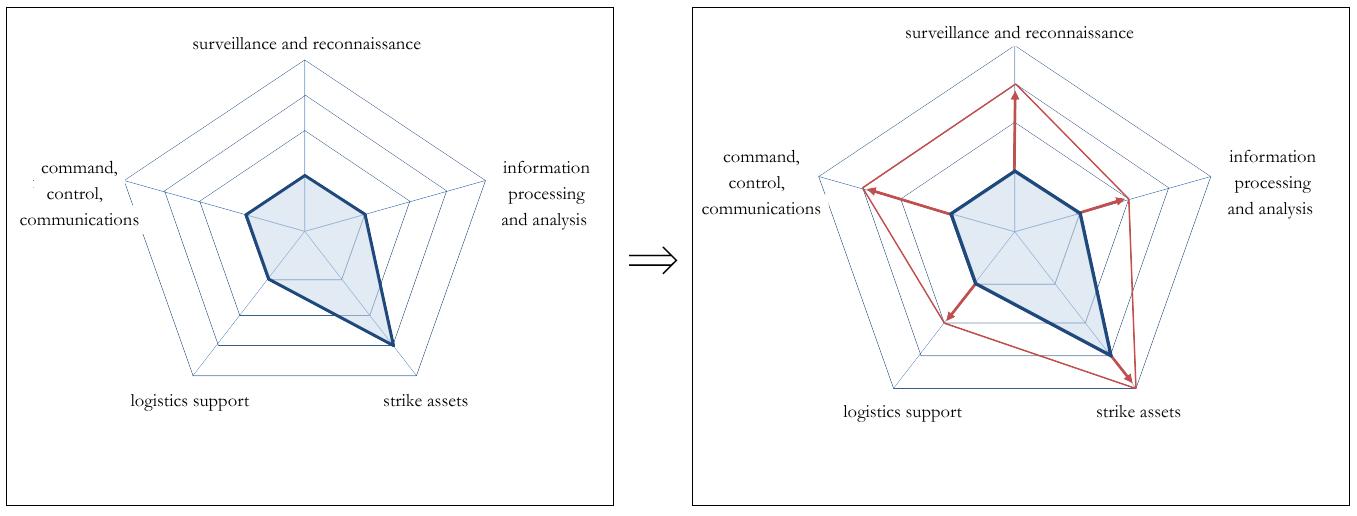

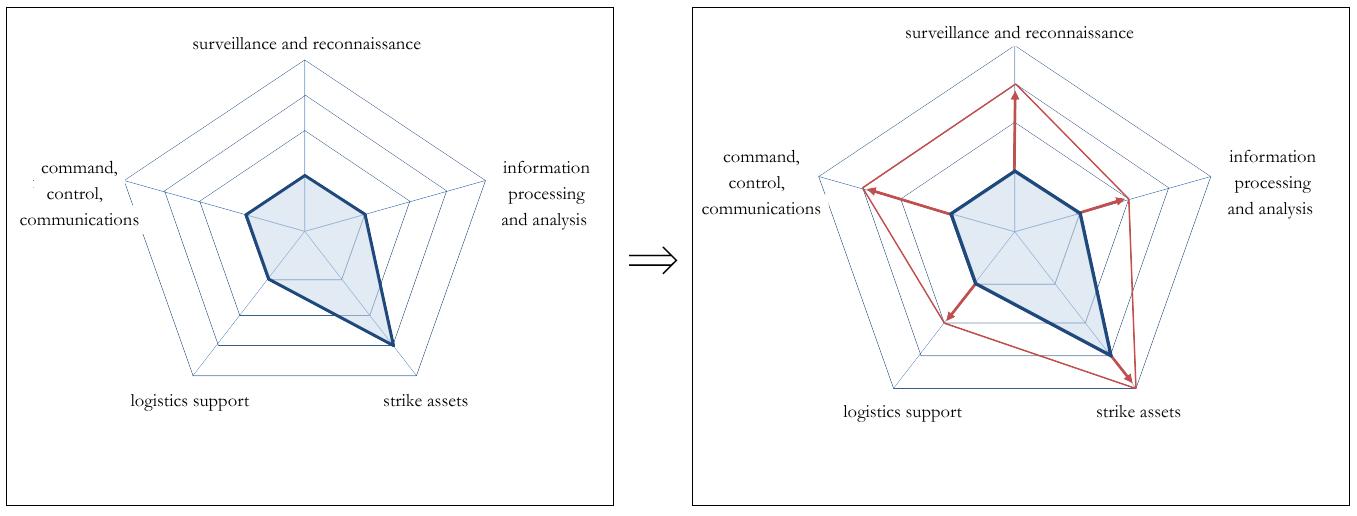

Drawing on the Russian case, five core capabilities can be abstracted as essential for implementing such a system: △surveillance and reconnaissance △information processing and analysis △strike assets △logistics support △command, control, and communications. As illustrated in [Figure 1], North Korea has thus far concentrated its efforts on expanding its strike assets, particularly nuclear warheads. With the exception of the most advanced technologies necessary for conducting direct strikes on the U.S. mainland, Pyongyang is assessed to have already secured a credible nuclear strike capability at the regional level.

[Figure 1]

However, as Kim Jong Un has stated, in order for nuclear force to function as part of a limited nuclear warfighting capability, it must possess not only destructive power but also precision and flexibility. From North Korea’s perspective, this necessitates △the development of advanced surveillance and intelligence-processing systems to enable effective targeting △the establishment of a reliable command and control architecture △the enhancement of resilient logistical support. Accordingly, it is evident that Pyongyang will prioritize the reinforcement of these relatively underdeveloped domains in its pursuit of a more balanced and integrated strategic capability.

Aligned with this trajectory, the next phase of North Korea’s effort to complete its reconnaissance-strike complex is likely to encompass the development of several key capabilities and weapons systems. In the domain of surveillance and reconnaissance, the regime is expected to invest in unmanned aerial vehicles, reconnaissance satellites, ground surveillance radar, and signals intelligence platforms. For information processing and analysis, priority will likely be given to the advancement of data analytics systems and automated battlefield target identification technologies. In the area of strike assets, where North Korea already demonstrates relatively advanced capabilities, further development is anticipated in multiple independently targetable reentry vehicles (MIRVs), reentry vehicle technologies, precision-guided munitions, and hypersonic missile systems. On the logistical front, the regime is expected to expand its inventory of mobile ammunition and fuel supply vehicles and to increase the deployment of transporter-erector-launchers. In terms of command and control, enhancements are likely to focus on mobile command centers, high-frequency and satellite communications infrastructure, and the development of more sophisticated cyber warfare capabilities (Smith and Bernstein 2022).

VI. South Korea’s Strategic Imperatives

North Korea’s 2025 promulgation of a “new line” of fortifying its nuclear forces may not be concretely articulated in the immediate term. Nevertheless, given the persistent nuclear threat posed by Pyongyang, it is imperative for Seoul to carefully examine the evolving priorities and objectives of the regime. Understanding the direction of these changes is particularly critical for assessing the state of strategic balance and deterrence between the two Koreas. Should North Korea shift from a focus solely on enhancing strike capabilities to addressing the operational vulnerabilities that constrain actual use, the regime would be departing from a path of positive nuclear learning and returning to the pursuit of offensive aims (Sohn 2023). In this context, South Korea must take deliberate steps to address its own strategic vulnerabilities and secure advantage within the emerging competitive landscape.

First, South Korea must secure strategic flexibility that transcends the debate over indigenous nuclear armament. While some advocate for the development of a domestic nuclear arsenal, such a path would entail significant costs in both practical effectiveness and normative legitimacy. Instead, Seoul should strategically leverage its advanced conventional capabilities and alliance-based extended deterrence framework to demonstrate normative leadership as a state capable of deterring nuclear threats without possessing nuclear weapons. This approach represents a strategic choice that simultaneously advances tangible security and international legitimacy, while also laying the foundation for the long-term sustainability of South Korea’s national security strategy.

Second, Seoul must construct a proactive defense architecture that reflects ongoing technological advancements. As North Korea reorganizes its military around the objective of operational completeness in nuclear warfare, encompassing preemption, retaliation, command and control, and logistical support, it is imperative for Seoul to move beyond the incremental enhancement of individual platforms and prioritize the establishment of an integrated force structure. This requires not only the effective linkage of reconnaissance assets such as UAVs, satellites, and electronic warfare systems with long-range precision strike capabilities, but also the simultaneous fusion of command, control, communications, computers, intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (C4ISR) systems. The resulting framework should not be construed as a narrow preemptive strike capability, but rather as a comprehensive, real-time response system capable of supporting sustained deterrence and defense operations.

Third, the ROK-U.S. joint nuclear planning and operational framework must be significantly strengthened. In response to the operational deployment of North Korea’s tactical nuclear weapons, the institutionalization of the Nuclear Consultative Group (NCG) is essential for advancing a fully developed system of joint planning and operations. This effort must move beyond basic information sharing to realize a three-stage structure comprising joint planning, joint decision making, and joint execution. Such a framework can be formalized through revisions to existing combined operational plans and further evolution of the tailored deterrence strategy. In particular, under the concept of nuclear-conventional integration, the restructuring of the allied command architecture must proceed in tandem with the integration of South Korea’s Three-Axis System (Sohn 2025).

Fourth, South Korea must establish an integrated operational strategy that unifies its diplomatic, military, and unification policy instruments. As North Korea leverages its nuclear capabilities not only as a tool of military deterrence but also as diplomatic leverage, Seoul is compelled to move beyond fragmented military responses and construct a comprehensive strategic framework. The sustainability and political effectiveness of sanctions, the strategic utility of policy tools, and their interplay with military deterrence all necessitate the simultaneous employment of multifaceted deterrence options. These include measures across the domains of intelligence, cyber operations, diplomacy, and economic pressure. This approach represents an expanded form of integrated deterrence, requiring the structuring of complementarities and feedback loops among all instruments of national power.

Fifth, South Korea must recalibrate its multilateral security cooperation framework. The emerging alignment among Russia, North Korea, and China is reshaping the strategic landscape of Northeast Asia by constructing a new bloc structure. In response, Seoul should not only reinforce the existing trilateral security partnership with the United States and Japan, but also broaden strategic linkages with NATO, Australia, the Philippines, and other middle-power states to build a multilayered deterrence network. This network would serve as a foundation for integrating military and non-military tools alike, and would be essential to realizing the concept of network-based extended deterrence. By assuming the role of a planner in the formation of such coalitions, South Korea can enhance both its strategic influence on the global stage and the credibility of its deterrent posture. ■

References

강혜석. 2024. “신냉전과 한반도 적대의 시대: 적대적 두 국가론 vs. 8.15통일독트린.” 『한국과 국제정치』40, 4: 35-66.

권숙도. 2024. “적대적 두 국가 개념을 통해 본 북한 통일정책의 전환.” 『대한정치학회보』32, 4: 127-150.

김태현. 2024. “북한 김정은의 기회주의적 군사전략.” 『국가전략』30, 4: 161-186.

김태현. 2024. “북한의 공세적 핵전략과 일반 핵강제.” 『전략연구』31, 3: 107-151.

손한별. 2023. “핵무기 개발과 국가행위의 변화: 파키스탄의 핵학습과 핵태세 변화를 사례로.” 『전략연구』30, 3: 221-251.

손한별. 2025. “핵-재래식 통합(CNI)의 개념과 구조: 한미동맹의 CNI 구현을 위한 함의.”『국가안보와 전략』25, 1: 119-155.

이중구. 2024. “북한의 적대적 두 국가론과 남북관계 전망.” 『통일정책연구』33, 1: 29-54.

정대진. 2024. “북한의 적대적 두 국가론과 남한의 통일방안.” 『통일과 평화』16, 2: 127-167.

조장원. 2025. “북한의 주요 군사동향: 2024년 평가 및 2025년 전망.” 『세종정책브리프』. 세종연구소.

함형필. 2021. “북한의 핵전략 변화 고찰: 전술핵 개발의 전략적 함의.” 『국방정책연구』37, 3: 7-43.

홍승욱. 2025. “미 DIA, 북, 2035년 ICBM 50기 보유 가능성.” 「자유아시아방송」. 5월 14일. https://www.rfa.org/korean/in-focus/2025/05/14/dia-north-icbm-2035-increase/.

Associated Press(AP). 2025. “North Korea’s Kim Says He’ll ‘Unconditionally Support’ Russia’s War Against Ukraine.” June 5. https://apnews.com/article/russia-shoigu-sergei-north-korea-ab1061c2e1eab58797996fc8e98c870f.

Davenport, Kelsey. 2020. “North Korea Parades New Missile.” Arms Control Association. November. https://www.armscontrol.org/act/2020-11/news/north-korea-parades-new-missile.

Grau, Lester W. and Charles K. Bartles. 2018. “The Russian Reconnaissance Fire Complex Comes of Age.” Changing Character of War Centre, University of Oxford, May 2018, https://static1.squarespace.com/static/55faab67e4b0914105347194/t/5b17fd67562fa70b3ae0dd24/1528298869210/The+Russian+Reconnaissance+Fire+Complex+Comes+of+Age.pdf.

Korean Central News Agency(KNCA). 2025. “Statement of Chief of External Policy Office of DPRK Foreign Ministry.” January 17. https://kcnawatch.org/newstream/1737067083-986473206/press-statement-of-chief-of-external-policy-office-of-dprk-foreign-ministry/.

Larison, Daniel. 2019. “The ‘Libya Model’ Killed the Hanoi Summit.” The American Conservative. March 30. https://www.theamericanconservative.com/the-libya-model-killed-the-hanoi-summit/.

National Committee on North Korea. 2018. “DPRK Report on the Third Plenary Meeting of the Seventh Central Committee of the Workers’ Party of Korea.” April 20. https://www.ncnk.org/resources/publications/dprk_report_third_plenary_meeting_of_seventh_central_committee_of_wpk.pdf.

Reuters. 2025. “North Korean Leader Kim Jong Un Vows to Further Develop Nuclear Forces.” February 8. https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/north-korean-leader-kim-jong-un-vows-further-develop-nuclear-forces-2025-02-08/.

Reuters. 2025. “North Korea Says US Nuclear Submarine at South Korea Port Posing GraveThreat, KCNA Reports.” February 11. https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/north-korea-says-us-nuclear-submarine-south-korea-port-posing-grave-threat-kcna-2025-02-10/.

Reuters. 2025. “North Korea’s Kim Jong Un Leads Missile Test, Stresses Nuclear Force Readiness, KCNA Says.” May 8. https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/north-koreas-kim-jong-un-leads-missile-test-stresses-nuclear-force-readiness-2025-05-08/.

Reuters. 2014. “North Korea Condemns U.N., Threatens a ‘New Form’ of Nuclear Test.” March 30. https://www.reuters.com/article/world-north-korea-condemns-u-n-threatens-a-new-form-of-nuclear-test-idUSBREA2T040/.

Seo, Ji-Eun. 2025. “Miffed North Korea Mocks Denuclearization as ‘Failed Old Dream’ after Trilateral Joint Statement” Korea JoongAng Daily, February 18.https://koreajoongangdaily.joins.com/news/2025-02-18/national/northKorea/Miffed-North-Korea-mocks-denuclearization-as-failed-old-dream-after-trilateral-joint-statement/2244685.

Sohn, Hanbyeol. 2023. “The Lessons North Korea Draws from the War in Ukraine.” Korea Economic Institute of America(KEI) Commentary. May 3.

Scott, Snyder. 2013. “The The Motivations Behind North Korea’s Pursuit of Simultaneous Economic and Nuclear Development.” Council on Foreign Relations. November 20. https://www.cfr.org/blog/motivations-behind-north-koreas-pursuit-simultaneous-economic-and-nuclear-development.

Smith, Shane and Paul Bernstein. 2022. “North Korean Nuclear Command and Control: Alternatives and Implications.” Defense Threat Reduction Agency.

Tertrais, Bruno. 2021. “Principles of Nuclear Deterrence and Strategy.” NATO Defense College Research Paper 19, 1-70.

Howell, Edward. 2020. “The juche H-bomb? North Korea, nuclear weapons and regime-state survival Get access Arrow.” International Affairs 96(4): 1051-1068.

■ Hanbyeol SOHN is Professor in the Department of Strategic Studies at Korea National Defense University (KNDU).

■ Translated and edited by Chaerin KIMResearch Assistant

For inquiries: 02 2277 1683 (ext. 208) | crkim@eai.or.kr