Does North Korea’s Recent Positive Growth Signal a Recovery in People’s Livelihoods?

- Commentary

- September 24, 2025

- Seungho JUNG

- Associate Professor, School of Northeast Asian Studies at Incheon National University

Seungho Jung, an Associate Professor of the School of Northeast Asian Studies at Incheon National University, analyzes the possibility that livelihoods of the North Korean people have worsened despite overall economic growth. Professor Jung assesses that a surge in consumer prices and the regime’s strengthened control on the economy suggest that the economic conditions affecting livelihoods have not recovered to their pre-pandemic standard. However, because these difficulties are unlikely to bring about immediate cooperation with the South, the author recommends that the South Korean government consider backing international organizations to support the North Korean people, instead of direct talks with the North Korean regime.

■ See Korean Version on EAI Website

1. Background

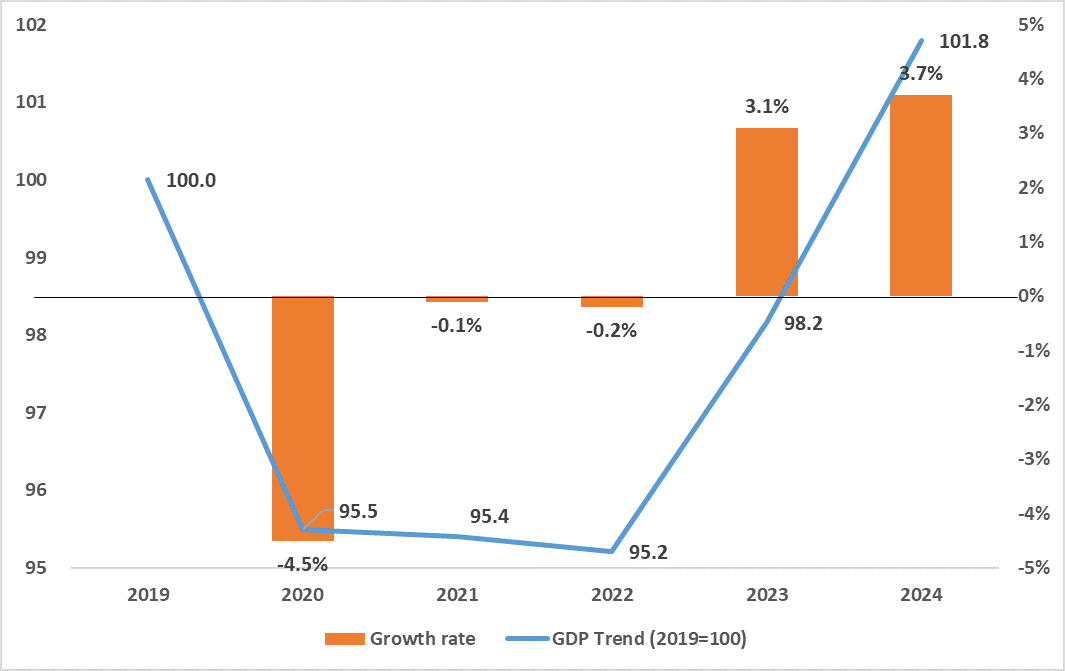

According to the Bank of Korea’s report, Gross Domestic Product Estimates for North Korea in 2024, released in August 2025, North Korea’s economy is estimated to have grown by 3.7% in 2024.[1] This is the highest rate since 2005 (3.8%) and marks the second consecutive year of positive growth following 3.1% in 2023. Indexing North Korea’s 2019 GDP—the year just before the COVID-19 pandemic— at 100 and applying the Bank’s annual growth estimates yields 101.8 for 2024, suggesting that output has surpassed its pre-pandemic level (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. North Korea’s growth rate (right axis) and GDP index (2019=100; left axis) since the COVID-19 pandemic.

Source: Bank of Korea

This raises the question: have North Koreans’ livelihoods—as the GDP path might suggest—returned to their pre-pandemic level? A review of recent market price trends and policy actions by the North Korean authorities suggests that, if anything, livelihoods may have deteriorated. Accordingly, this commentary analyzes recent changes in the living conditions of the North Korean populace by focusing on North Korea’s market indicators—such as the exchange rate and grain prices—and the North Korean authorities’ ongoing post-pandemic centralization policy.

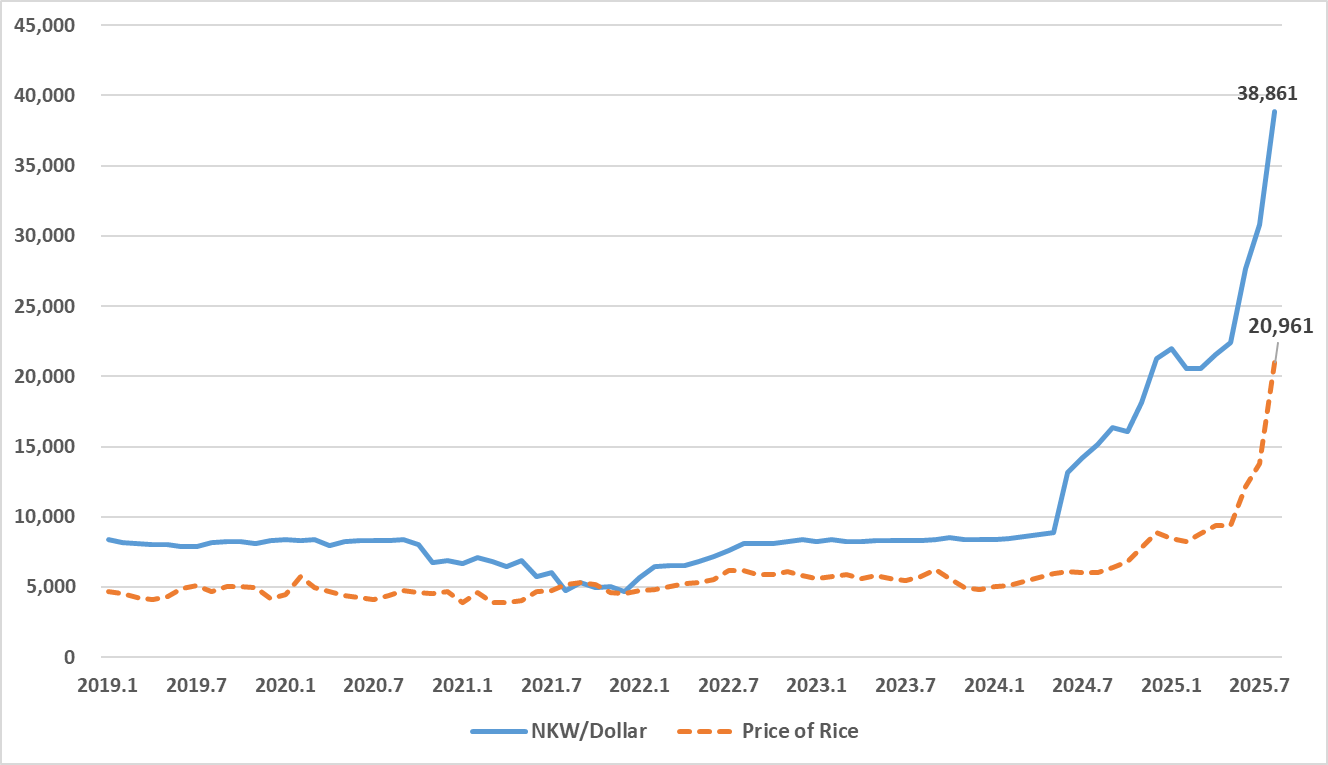

2. A Surge in Market Prices

First, we examine market prices, which are most closely tied to livelihoods. In North Korea today, the price trend is better characterized as a “surge” than a mere “increase.” The market exchange rate for the North Korean won (NPW) against the U.S. dollar (USD) stood at 38,861 won per USD as of August 2025. The rice price—a proxy for market prices—was 20,961 won, exceeding the 20,000-won threshold (see Figure 2). These levels represent a renewed spike not seen since around 2013, when market prices began to stabilize following the turmoil after the failed 2009 currency reform. During that stabilization period, the dollar rate hovered around 8,000 won per USD and the price of rice revolved around 5,000 won; by comparison, current levels are more than four times their long-run averages.

Figure 2. Trends in the market exchange rate (NPW/USD) and rice price since 2019

Source: DailyNK 「North Korea Market Trends」

Policies by the North Korean regime appear to have played a major role in this run-up. Lim (2025) points to the April 2024 ban on the use of foreign currency and the resulting loss of confidence in the government’s FX policy as key drivers.[2] Choi (2024) highlights revisions since 2000 to the Fiscal Law, the Electronic Payments Law, and the Central Bank Law—along with tighter state control over currency circulation—as background factors.[3] While not directly verifiable with available data, the possibility of monetary expansion has also been raised. According to AsiaPress and RFA, nominal monthly wages for workers in major sectors reportedly rose by 10–40 times from late 2023.[4] If, in the absence of adequate fiscal resources, the wage increases were financed through money creation, the resulting expansion of the money supply could have triggered rapid inflation. Whatever the cause, the sharp rise in prices is increasing household burdens and worsening livelihoods.

3. Strengthening Centralized Control over the Economy

Alongside rising prices, another factor burdening livelihoods is the North Korean authorities’ tightening of centralized control over the economy. Since the collapse of the Hanoi U.S.–DPRK summit in 2019 and through the COVID-19 period, the policy stance has shifted from expanding market autonomy to reinforcing state control. The wholesale and retail sector—especially grain distribution and consumer-goods retail—has been a principal target.

In the grain sector, the Grain Management Law (yangjeongbeop) was amended three times (2020, 2021, 2022), legally codifying the state’s authority to sell grain. Subsequent measures banned grain sales in markets and permitted sales only through state-run grain outlets (yanggok panmaeso). Similarly, amendments to the Socialist Commerce Law in 2021 expanded the state’s retail functions. According to defector testimonies and media reports, from this period market opening hours and lists of permitted items were restricted, while the distribution of consumer goods was steered away from markets toward state-run distribution channels and state stores—in effect, shifting flows from open markets to the state distribution system.

Given that a large share of households has relied on market transactions for their livelihoods, these policies can pose a direct threat to incomes.[5] For example, when grain sales are prohibited, not only grain vendors but also related livelihoods—such as transport and processing (e.g., rice-cake and liquor production)—are stifled. In turn, such measures increase inefficiencies in grain distribution, constrain market supply, and can further amplify the price pressures discussed in Section 2. Moreover, many grain outlets and state stores are, effectively, operated by private actors who lease premises from the state. This structure tends to raise incomes for those with political ties to state bodies or sufficient capital to secure leases, while reducing the earnings of petty traders who pay stall fees in markets. As a result, market-based livelihood opportunities shrink, and income inequality is likely to widen.

4. A Possible Shift in the Growth–Livelihood Relationship

Recent developments in North Korea suggest a possible shift in the relationship between the GDP growth rate and household livelihoods. In the early 2000s, as marketization expanded, the two generally moved in the same direction; in some cases, improvements in living standards may even have outpaced measured growth. This may be because the Bank of Korea’s growth estimates are based primarily on output in the official economy and have difficulty capturing production in the informal economy. For example, data from South Korea’s Ministry of Unification’s, Report on North Korea's Economy and Society as Perceived by 6,351 Defectors, the share of respondents reporting three meals a day rose from 56.3% before 2011 to 89.7% after 2012—an increase of more than 30 percentage points.[6]

More recently, however, this correlation appears to have weakened. The Bank of Korea’s 2024 estimates indicate that expansion was concentrated in state-led activities—heavy and chemical industries (10.7%) and construction (12.3%)—driven by war-related demand linked to the Russia–Ukraine conflict and a policy focus on rural housing construction. In contrast, livelihood-linked sectors—light industry (−0.7%) and agriculture, forestry, and fisheries (−1.9%)—contracted. Even when production expands or foreign-currency earnings increase due to war and related factors, the gains tend to accrue to the North Korean authorities rather than to households. The recent pattern of foreign-currency inflows tells the same story. For example, proceeds from cryptocurrency hacking primarily expand the regime’s hard-currency resources and are unlikely to translate into improvements in livelihoods.[7] In short, both war-related windfalls and cryptocurrency proceeds are more likely to culminate in an expansion of the regime’s revenues than to benefit household livelihoods.

Overall, despite recent positive growth, North Korean households’ livelihoods likely remain below pre-pandemic levels. The centralization policy can be read as an attempt to capture available resources amid international sanctions and pandemic-related uncertainty. While this approach may yield short-term gains in administrative control or specific policy outcomes, over time it is likely to impose rising costs in the form of economic inefficiency and setbacks to household livelihoods—something the North Korean authorities should be mindful of.

5. Policy Implications

Even if North Korea’s economy related to livelihoods remains strained, the likelihood of inter-Korean cooperation based on this issue is unlikely to materialize in the near term. During the COVID-19 border closure, North Korea rejected the South Korean government’s offers of medical and livelihood assistance. More recently, in her July 28 statement, Kim Yo Jong, Deputy Department Director of the Workers’ Party of Korea (WPK), reaffirmed Pyongyang’s negative stance, declaring that “there is nothing to discuss with South Korea.”

Accordingly, at this stage, the South Korean government should prioritize support through international organizations rather than direct cooperation with North Korea. Data from the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (UN OCHA) Financial Tracking Service (FTS) show that humanitarian assistance to North Korea in 2024 amounted to a low figure of USD 2.8 million—a drop of over 90% from USD 45.9 million in 2019, the last year before the pandemic.[8] Donor countries have been limited mainly to Switzerland, Sweden, and Norway. With international organizations and NGOs resuming activities following the lifting of border restrictions, the South Korean government should actively back these efforts.

At the same time, in the longer term, Seoul should continue to signal a willingness to cooperate on livelihood issues, keeping in mind the possibility of shifts in Pyongyang’s position. However, it should avoid rushing to pursue high-level talks or visible outcomes. Such an approach risks giving an impression of being swayed by North Korea, which could in turn fuel domestic backlash against humanitarian assistance to North Korea. ■

[1] Bank of Korea. (2025). Gross domestic product estimates for North Korea in 2024. https://www.bok.or.kr/eng/...400423

[2] Lim, S. H. (2025). The background and implications of the recent re-spike in North Korea’s market exchange rate and prices. Institute for National Security Strategy (INSS). [in Korean] https://www.inss.re.kr/publication/bbs/ib_view.do?nttId=41037505&bbsId=ib

[3] Choi, J. Y. (2024). North Korea’s strengthening of the state distribution policy and changes in market indicators (Online Series CO 24-68). Korea Institute for National Unification (KINU). [in Korean] https://www.kinu.or.kr/main/...=127918

[4] AsiaPress. (2024, January 5). Inside North Korea: A more-than-tenfold “wage increase” (1)—Wages at state-owned enterprises and among public officials raised across the board, yet monthly take-home remains around 4,500 won. [in Korean] https://www.asiapress.org/korean/2024/01/nk-economys/wage-increase/; Radio Free Asia. (2024, January 9). North Korea raises workers’ wages and food-ration prices simultaneously on a trial basis. [in Korean] https://www.rfa.org/korean/...01092024091414.html; Radio Free Asia. (2024, April 29). North Korea fully implements a 20-fold wage increase for factory workers. [in Korean] https://www.rfa.org/korean...04292024095034.html

[5] According to a survey conducted by the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) of residents actually living in North Korea, market-based income accounts for at least 75% of North Korean household income. Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS). (2024). Paradise evaporated: Escaping the no-income trap in North Korea. https://beyondparallel.csis.org/paradise-evaporated-escaping-no-income-trap-north-korea/

[6] Ministry of Unification. (2024). Report on North Korea’s economy and society as perceived by 6,351 defectors [in Korean] https://unikorea.go.kr/books/...=47397&category=&pageIdx=

[7] According to the UN Panel of Experts, North Korea is estimated to have stolen more than $3 billion through cryptocurrency hacking between 2017 and 2023. United Nations Security Council. (2024). Final report of the Panel of Experts submitted pursuant to resolution 2680 (2023) (S/2024/215). https://undocs.org/...;DeviceType=Desktop

[8] https://fts.unocha.org/countries/118/summary/2024

■ Seungho JUNG is an Associate Professor at the School of Northeast Asian Studies, Incheon National University.

■ Translated and edited by Inhwan OH, Senior Research Fellow; Jonghyuk CHUNG, Researcher, Korea National Diplomatic Academy

For inquiries: 02 2277 1683 (ext. 202) | ihoh@eai.or.kr