North Korea’s Garbage-filled Balloons as a New Psychological Warfare

- Commentary

- February 18, 2025

- Nilay TAVLI

- PhD student, Hanyang University

- Kyung-young CHUNG

- Professor, Hanyang University

Nilay Tavli (PhD student, Hanyang University) and Kyung-young Chung (Professor, Hanyang University) examine the evolving nature of North Korea's unconventional warfare tactics, focusing on the regime's recent use of balloon provocations and the resultant psychological threats to South Korea. They recommend Seoul enhance its defense capabilities and mitigate biological warfare risks, while curbing the distribution of leaflets to the North to alleviate tensions. The authors emphasize a shift in North Korea’s approach to inter-Korean relations and underscore the necessity for a proactive, comprehensive strategy to protect South Korea’s national security and public health.

From May 28, 2024 to November 28, 2024, North Korea intensively conducted garbage-filled balloon operations against South Korea. These provocations had significant psychological effects on the South Korean government, military, and the public. In contrast to the high-tech surveillance balloons reportedly deployed by the People’s Republic of China (PRC) toward the U.S. in May 2023, and previous balloon provocations between the two Koreas, North Korea’s use of garbage-filled balloons represent a low-tech tactic strategy. This approach is interpreted to be designed to humiliate and instill fear within South Korean society by degrading national dignity and pride. Furthermore, these actions reveal North Korea’s unconventional warfare tactics, distinct from Weapons of Mass Destruction (WMD) or nuclear and missile tests. The environmental risks and potential chemical or biochemical threats underscore the necessity for Seoul to expand its defense strategies and enhance communication channels with the public to mitigate social anxiety.

To provide a comprehensive understanding, this study begins by addressing sovereignty, the right of self-defense, and the Korean War Armistice Agreement concerning military provocations crossing the border. This includes analyzing the differences between balloon provocations by North Korea and China and examining the historical context of such provocations. By discussing these incidents, the study defines the key characteristics of these provocations in terms of motivations, content, and techniques. The psychological impact of these balloons is meticulously examined, as the inclusion of refuse amplifies their psychological effects, along with the Two Hostile States proclaimed by North Korea. Additionally, the study explores the broader implications and concerns of potential biological warfare risks, including their impact on South Korean society, the environment, and inter-Korean relations. Ultimately, it presents conclusions with policy recommendations to address this evolving threat.

I. Sovereignty and the Right of Self-Defense

A country’s sovereignty extends to its territory, territorial waters, and airspace, so the entry of a foreign aircraft or balloon into its airspace without the permission of that state is itself a violation of sovereignty. All Members of the United Nations shall refrain in their international relations from the threat or use of force against the territorial integrity or political independence of any state, or in any other manner inconsistent with the Purposes of the United Nations (United Nations Charter, Chapter I; Lim 2024).

Nothing in the present Charter shall impair the inherent right of individual or collective self-defense if an armed attack occurs against a Member of the United Nations, until the Security Council has taken measures necessary to maintain international peace and security. Measures taken by Members in the exercise of this right of self-defense shall be immediately reported to the Security Council and shall not in any way affect the authority and responsibility of the Security Council under the present Charter to take at any time such action as it deems necessary in order to maintain or restore international peace and security (United Nations Charter, Chapter VII).

Under international law, the International Court of Justice recognizes the right of self-defense against the use of force, as stipulated in Article 51, Chapter VII of the UN Charter. This provision permits a state to exercise self-defense in response to an armed attack.

In particular, the Korean War Armistice Agreement between the Commander-in-Chief, United Nations Command, on the one hand, and the Supreme Commander of the Korean People’s Army and the Commander of the Chinese People’s Volunteers, on the other hand, clearly addresses that neither party shall execute any hostile act within, from, or against the demilitarized zone (The Korean War Armistice Agreement 1953).

II. Comparison of Balloon Provocations between North Korea and China

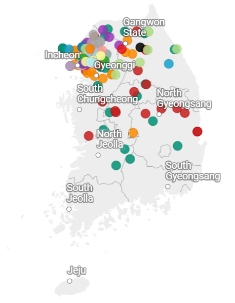

Between May 8, 2024, and November 28, 2024, North Korea conducted a series of provocations by launching balloons filled with refuse into South Korea. By the conclusion of the 30th wave, it was estimated that North Korea sent between 3,097 (landing successfully) and 8,870 balloons. In total, balloons landed in 3,359 locations across South Korea, including Seoul, Incheon, Gangwon, Gyeonggi, North and South Chungcheong, North Gyeongsang, and North Jeolla Province (Cha and Lim 2024).

In contrast, China launched a “spy balloon” toward the U.S. border on February 2, 2023 (Stewart and Mason 2023). A Chinese-made unmanned balloon flew near the Malmstrom Air Force Base in Montana, where nuclear missile silos are located.

Specifically, North Korea intensified its use of garbage-filled balloons starting in September 2024. The frequency of these launches was as follows: 2 days in May, 9 days in June, 4 days in July, 2 days in August, and 12 days in September.

Figure 1. Locations of North Korea’s Garbage-Filled Balloons Landings Identified in South Korea

*Source: CSIS, “North Korea’s Garbage-Filled Balloons,” https://beyondparallel.csis.org/map-of-north-koreas-garbage-filled-balloons/

The relatively low number of balloons sent by North Korea may be attributed to the severe flooding along the Amnok (Yalu) River that occured in the summer of 2024. Following recovery efforts, the regime intensified its use of garbage-filled balloons as a provocation tactic (Hankyoreh 09/25/2024). Kim Jong Un led rescue operations for approximately 5,000 isolated residents near the river, with over 4,200 individuals saved with the assistance of pilots. The damage was attributed to inadequate infrastructure and poverty (The Korea Times 7/29/2024).

Balloon-based propaganda has been a long-standing tactic between the two Koreas, dating back to the Cold War era. Previously, both governments engaged in sending balloons containing ideological leaflets; however, Seoul ceased sending balloons toward the North following the inter-Korean agreement in June 2004. Therefore, balloons recently sent to North Korea were primarily by North Korean defectors and activist groups, rather than the South Korean government.

In 2020, the Moon Jae-in administration enacted a ban on activist groups launching balloons filled with propaganda materials, such as leaflets, Bible verses, DVDs, and USBs, towards the North. However, the “Ban on Anti-North Korea Propaganda Leaflets” decision was overturned in 2021 (King 2024; Yim 2024). The Republic of Korea (ROK) Constitutional Court deemed the ban an excessive restriction on freedom of expression, viewing it as a violation of South Korea’s democratic principles.

The ROK Joint Chiefs of Staff said, “As North Korea’s garbage balloon spraying provocations have been prolonged, some have called for physical responses, such as shooting down the balloons in the air. However, if aerial shooting causes the unexpected spread of hazardous substances, it could cause serious harm to the safety of our people.” They further emphasized that they would take resolute military measures if it is judged that serious harm to public safety has occurred or that a red line has been crossed (Yonhap News 9/23/2024).

In the meantime, the U.S. shot down balloons by F-22A on Feb 4, 2023. China claimed that an alleged spy balloon spotted over the U.S. was a Chinese “civilian airship” which had deviated from its planned route (BBC 2/4/2023). The U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken and China’s Foreign Minister Wang Yi held a meeting on the sidelines of the Munich Security Conference on Feb 18, 2023. Blinken “directly spoke to the unacceptable violation of U.S. sovereignty and international law by the PRC high-altitude surveillance balloon in U.S. territorial airspace, underscoring that this irresponsible act must never again occur” (U.S. Department of State 2023). On the other hand, Wang Yi “pointed out that what the U.S. side has done was apparently an abuse of the use of force and violation of customary international practice and the International Civil Aviation Covenant” (RFA 2/21/2023).

North Korea’s balloon provocations against South Korea and PRC’s alleged balloon activities against the United States differ in purpose, context, and technology. Pyongyang employed balloons, often filled with propaganda materials, trash, or other disruptive materials, as low-tech tools of psychological warfare and ideological conflict. These actions reflect deeply seated animosities, serving a cost-effective means of provocation. In contrast, China’s balloons, as alleged by the U.S., were high-tech surveillance devices equipped for intelligence gathering, indicating strategic geopolitical competition rather than ideological disputes. These activities underline the distinct tactical and strategic objectives of both nations.

Based on the United Nations Charter referenced earlier, balloons launched without permission can be considered a violation of sovereignty. In this context, the balloon incursions by North Korea and China constituted breaches of sovereignty.

The South Korean government refrained from shooting down North Korea’s balloons, citing the right of self-defense, while permitting North Korean defectors to send balloons instead. The U.S. exercised the right of self-defense over China’s balloon.

III. Intent of North Korea’s Balloon Provocations

While Pyongyang’s balloons intended to harm South Korean society by insulting, dividing, and intimidating it, South Korea’s anti-North Korean leaflets have aimed to provide external information.

Additionally, North Korea sent refuse-filled balloons to the South in an effort to prevent its defectors and private organizations from distributing leaflets that expose the truth about the Kim regime. It is estimated that Pyongyang’s balloon provocations sought to pressure Seoul into cracking down on the dissemination of information to North Korea (VOA 5/31/2024).

The continuous deployment of balloons suggests that North Korea has been gathering data to target specific areas for balloon drops, potentially using them in the event of war. Based on future balloon levitation data, it could be possible for Pyongyang to launch balloons containing biochemicals to a specific location.

When President Yoon Suk Yeol hosted the Polish President’s Welcome Ceremony on Oct 25, 2024, North Korea released a balloon containing leaflets criticizing President and Mrs. Yoon. Some of the leaflets landed on the grounds of the Presidential Office in Yongsan. This marked the 30th wave of North Korea’s trash-filled balloon provocations and the first instance in which it placed leaflets inside a balloon (Kyunghyangshinmoon 10/25/2024).

A closer examination of the landing sites of garbage-filled balloons in South Korea reveals that these areas are high-value targets, including the functionality of Seoul, military bases, and industrial complexes.

Although North Korea employed a less-developed balloon technology, it implies that Pyongyang has partially changed its warfare tactics. While North Korea has long prided itself on its nuclear weapons capabilities and advanced nuclear development, this time, it opted to send garbage-filled balloons instead of threatening Seoul with nuclear missile tests, as it typically has. Moreover, this new tactic was unpredictable, making it more difficult for Seoul to counter, as it could yield various outcomes (Yu 2024).

North Korea aimed to convey two messages through the balloon provocations. The first message was directed at the South Korean government, signaling Pyongyang’s ability to adopt new, unconventional warfare tactics as opposed to traditional methods. Additionally, it sought to message the South Korean people that Seoul should always be prepared for North Korea’s unconventional war tactics, thereby exacerbating social anxiety. Clearly, Pyongyang intended to create a scene where Seoul was incapable of protecting its citizens.

IV. Psychological Warfare: Two Hostile States

The 9th Plenary Meeting of the 8th Central Committee of the Ruling Workers’ Party of Korea, held from December 26 to 30, 2023, concluded that “the [inter-Korean] relationship has completely solidified into hostile relations, not ethnic or homogenous relations, but relations between two hostile states in a state of war” (Korean Central News Agency 12/31/2023). It further called for a “fundamental shift in the principles and direction of the struggle with South Korea.”

North Korea has never abandoned its goal of Korean unification, pursuing it through military means. Kim Jong Un has mobilized the North Korean people to prepare for a Unification War. In this context, the trash balloon operations are significant tactics to wage the war.

North Korea has garnered attention for its developed nuclear weapons capabilities. Kim Jong Un stated that the basic mission of North Korea’s nuclear arsenal is to deter war, while its secondary mission is to completely occupy the territory. In addition to advancing its nuclear weapons, North Korea has launched waste-filled balloons in a sustained campaign against the South. Through these provocations, Pyongyang aimed to demonstrate its ability and willingness to employ unexpected warfare tactics as an offensive countermeasure to the actions of hostile forces (King 2024).

The psychological impacts of waste-filled balloons include damaging South Koreans’ sense of respect, honor, dignity, and pride (Yu 2024). In addition to physical and environmental damages, insult and degradation have become key tools in North Korea’s provocations, aiming to damage South Korean people’s deep national identity.

In addition to these humiliating threats, North Korea desired to highlight its differences from South Korea. The balloons symbolize a clear dissociation between the two sides, signaling North Korea’s belief that unification is no longer possible and that decoupling is inevitable. Therefore, the balloons are emblematic of North Korea’s lack of hope for peace on the Korean Peninsula (Cha and Lim 2024).

Furthermore, the deployment of garbage-filled balloons represents a violation of fundamental human rights. All individuals have the right to live in a clean environment and feel secure. However, North Korea’s actions sought to undermine these basic needs (Cha and Lim 2024). Psychological and civil operations are designed to maximize fear, leading to social disruption. The psychological effects of these balloon provocations triggered environmental and health concerns among South Koreans (Kang and Kim 2024).

Health and environmental risks are another serious result of waste-filled balloon provocations. After Pyongyang sent a huge amount of waste, South Korea had to manage the situation carefully to prevent any potential contagious risks. However, this has become a new challenge for Seoul as garbage-filled balloons represent an unexpected form of warfare. Given that garbage-filled balloons have strategy, concept, and threat, they can be regarded as a form of warfare tactic (Association of the United States Army 2024).

On top of this, adding feces to the balloons should be thought of under the “biochemical terrorism” context (Kang and Kim 2024). Feces, as one of the most challenging forms of biochemical waste, can spread microorganisms and bacteria that act as catalysts for disease. Due to North Korea’s poor public health infrastructure, feces sent from the North could cause serious diseases. Biological agents could cause infections rapidly, potentially leading to a “chain reaction” similar to COVID-19 or MERS and heightening public security concerns.

Currently, there is no risk to public health. The South Korean government has handled the situation patiently and meticulously, with its Joint Chiefs of Staff overseeing technical parts of the waste and informing the public (Kang and Herskovitz 2024). Additionally, the South Korean military, along with the U.S. military, local police, and authorities, have worked together on cleanup and analysis (Guzman 2024).

Biological agents are more easily airborne than chemical agents, requiring different security measures. Unlike chemical or nuclear weapons, biological agents undergo aerosolization to maximize lethality through respiratory infections. Consequently, different preservation techniques are required for each type of agent to ensure civilian protection (Kang and Kim 2024).

To mitigate unforeseen circumstances, the South Korean military assigned ordnance units and chemical-biological warfare response teams. Additionally, to safeguard civilians from potential harm, Explosive Ordnance Disposal (EOD) teams, Chemical, Biological, Radiological, and Nuclear (CBRD) teams, and Cyber Rapid Response Teams (CRRT) were assigned (Kim and Shin 2024).

V. Conclusion and Policy Recommendations

North Korea’s recent use of garbage-filled balloons marks a notable shift in its psychological and unconventional warfare tactics against South Korea. While balloon provocations have historical roots in inter-Korean tensions, the content and intent of these recent incidents illustrate an evolving strategy of Pyongyang. By replacing traditional propaganda leaflets with waste materials, North Korea has sought to amplify psychological distress, environmental harm, and public anxiety in the South. Unlike its prior threats centered on nuclear tests and military aggression, this new tactic is unpredictable, cost-effective, and difficult to counter, demonstrating Pyongyang’s adaptability in asymmetric warfare. Moreover, the balloons not only serve as a symbol of animosity but also highlight the deteriorating state of inter-Korean relations, revealing North Korea’s intent to distance itself further from any prospects of reconciliation.

In addition to the psychological impact, the introduction of biological risks through waste-filled balloons raises serious concerns about public health and environmental security. The discovery of parasites and the potential for bacterial transmission underscore the hidden dangers of this form of provocation. The incident calls for enhanced biosecurity measures and a coordinated response strategy involving military, law enforcement, and public health institutions. Ultimately, North Korea’s use of biological and psychological tactics signals a broader shift in its approach to conflict, requiring South Korea to adopt a multifaceted defense strategy that prioritizes both public safety and diplomatic resilience.

The first recommendation is that ROK forces be prepared to take prompt action in the event of North Korea’s balloon provocation. If North Korea were to release a biochemical or smallpox virus via the garbage balloons, it could cause catastrophic fatalities and complications. A more proactive response is thus necessary. Balloons move slowly and according to wind direction, making them relatively easy to locate and track. Thus, upon the announcement of North Korea’s provocation, military countermeasures, such as intercepting flying objects north of the Military Demarcation Line (MDL) in consultation with the United Nations Command to shoot down balloons, should be taken (Lim 2024). Representatives of the Chinese people’s Volunteer Army and the Korean People’s Army, who withdrew in 1994, should return to the Military Armistice Commission in Panmunjom to manage the armistice agreement (Chung 2020).

The second recommendation is for South Korea to strengthen its military and defense systems, as recent balloon provocations have exposed vulnerabilities in the country’s air defense and radar capabilities. This issue requires immediate attention. Balloons are classified as “unpowered aircraft” and have been used as a tool for psychological and unconventional warfare. However, South Korea has primarily focused on nuclear deterrence and missile defense, often overlooking the threat posed by unpowered aerial objects. These balloons can bypass traditional air defense systems, making them difficult to track and control. Furthermore, the ROK military must assume a more proactive role. Recent provocations saw military involvement largely limited to post-event cleanup, rather than strategic deterrence and elimination. South Korea must send a clear message that its military is prepared to respond decisively, ensuring that North Korea understands the consequences of continued provocations.

The third recommendation addresses actions at the government level. While Seoul has officially condemned North Korea’s balloon provocations, further steps are needed to manage the situation effectively. South Korea ceased sending provocative balloons toward the North, yet some North Korean defectors and activist groups continue this practice, escalating tensions. These actions would not only provoke North Korea but also affect South Korean civilians, necessitating government intervention. Thus, Seoul must take a firm stance in monitoring and regulating these groups, while seeking cooperative solutions. (Park, Arranz, Huang, Gu, and Chowdhury 2024). ■

References

Association of the United States Army. 2024. “The Principles for the Future of Warfare and Stand-off Warfare.” April 22. https://www.ausa.org/publications/principles-future-warfare-and-stand-warfare.

BBC. 2023. “Chinese spy balloon over US is weather device says Beijing.” Feb 4. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-64515033

Bureau of Arms Control. 1953. “The Korean War Armistice Agreement.” July 27. https://2001-2009.state.gov/t/ac/rls/or/2004/31006.html

Cha, Victor and Andy Lim. 2024. “Garbage, Balloons, and Korean Unification Values.” Center for Strategic & International Studies (CSIS). July 1. https://www.csis.org/analysis/garbage-balloons-and-korean-unification-values

Chung, Kyung-young. 2020. South Korea: The Korean War, Armistic Structure, and a Peace Regime. LAMBERT Academic Publishing.

CSIS. “North Korea’s Garbage-Filled Balloons.” https://beyondparallel.csis.org/map-of-north-koreas-garbage-filled-balloons/

Guzman, de Chad. 2024. “Crap Attack: North Korea Sends Balloons Carrying Trash and Poop to South Korea.” Time. May 29. https://time.com/6983012/north-korea-south-balloons-trash-feces-propaganda/

Hankyoreh. 2024. “Data Shows North Korea’s Trash Balloons Aren’t Mere One-sided Provocations.” September 25. https://english.hani.co.kr/art i/englishedition/enorthkorea/1159 717.html

Kang, Kyeong-ho and Hyun-jung Kim. 2024. “Assessing the Biochemical Threats of North Korea’s ‘Trash Balloon’ Provocations.” Institute for National Security Strategy (INSS) Issue Brief 109, 6.

Kang, Shin-hye and John Herskovitz. 2024. “South Korea Warns of Parasites as North Sends More Trash- and Poop-Filled Balloons.” Time. June 2025. https://time.com/6991474/north-south-korea-trash-balloons-parasites/

Kim, Jeong-min. 2024. “Defector Attempts to Send BTS Songs to North Korea in Latest Leaflet Launch.” NK News. May 13. https://www.nknews.org/2024/05/defector-attempts-to-send-bts-songs-to-north-korea-in-latest-leaflet-launch/

King, Robert. 2024. “Crap Attack” Against South Korea: North Korea Sends Balloons Carrying Trash Across the DMZ.” KEI. June 11. https://keia.org/the-peninsula/crap-attack-against-south-korea-north-korea-sends-balloons-carrying-trash-across-the-dmz/.

Korean Central News Agency (KCNA). 2023. “Report on 9th Enlarged Plenum of 8th WPK Central Committee.” Dec 31.

Kyunghyangshinmoon. 2024. "Polish President’s Welcome Ceremony Drops ‘Leaflet Criticizing President Yoon and His Wife.’” October 25. https://www.khan.co.kr/article/202410250600035

Lee, Jung-joo. 2024. “NK Sends Over 1,000 Trash Balloons to S. Korea in last 5 days.” The Korea Herald. https://www.koreaherald.com/mobile/khpad_view.php?ud=20240908050098.

Lee. Min-ji. 2024. “N. Korean Defectors Send Balloons Carrying Anti-Pyongyang Leaflets to North.” Yonhap News Agency. May 13. https://en.yna.co.kr/view/AEN20240513002851315

Lim, Yun-gap. “North Korea's Garbage Balloon and the Problem of Aggression and the Right to Self-Defense.” Military Commentary 120, Winter 2024.

Park, Ju-min, Adolfo Arranz, Han Huang, Jackie Gu, and Jitesh Chowdhury. 2024. “Balloon Offensive.” Reuters. June 11. https://www.rfa.org/english/news/china/blinken-wang-yi-02212023 040645.html.

RFA. 2024. “Blinken tells China’s top diplomat balloon ‘unacceptable violation of US sovereignty.’” Feb 21. https://www.whitehouse.gov/remarks/2025/01/the-inaugural-address/

The Korea Times. 2024. “N. Korea’s Kim Guides Rescue Operation for Residents in Flood-hit Areas.” June 29. https://www.koreatimes.co.kr/www/nation/2025/01/103_379516.html

United Nations. “United Nations Charter.” https://www.un.org/en/about-us/un-charter/full-text.

U.S. Department of State. 2023. “Secretary Blinken’s Meeting with People’s Republic of China (PRC) Director of the CCP Central Foreign Affairs Office Wang Yi.” February 18. https://2021-2025.state.gov/secretary-blinkens-meeting-with-peoples-republic-of-china-prc-director-of-the-ccp-central-foreign-affairs-office-wang-yi/.

VOA. 2024. “Experts: North Korea’s Dirty Balloon Spraying Is a ‘Trick’ to Stop Leaflets Against North Korea.” May 31.www.voakorea.com/a/7636710.html

Yim, Hyun-su. 2024. “South Korea Court Strikes Down Ban on Anti-North Korea Propaganda Leaflets.” Reuters. September 26. https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/south-korea-court-strikes-down-ban-anti-north-korea-propaganda-leaflets-2023-09-26/.

Yu, Ji-hoon. 2024. “The Significance and Implications of North Korea’s Garbage Balloon Tactics.” The Diplomat. August 13. https://thediplomat.com/2024/08/the-significance-and-implications-of-north-koreas-garbage-balloon-tactics/.

■ Nilay TAVLI is a PhD student at Hanyang University’s Graduate School of International Studies.

■ Kyung-young CHUNG is an adjunct Professor at Hanyang University’s Graduate School of International Studies.

■ Edited by: Sheewon Min, Research Associate

For inquiries: 02 2277 1683 (ext. 209) | swmin@eai.or.kr