Rethinking Nuclear Negotiations: The Impact of Diplomatic Phases on DPRK’s Strategic Behaviors

- Commentary

- April 29, 2024

- Sang Ki KIM

- Research Fellow, Korea Institute for National Unification

Sang Ki Kim, a researcher at the Korea Institute for National Unification, analyzes the patterns of North Korea’s nuclear and missile test activities during the past negotiation and deadlock phases, and concludes that nuclear negotiations have been instrumental in postponing the development of DPRK’s weapon programs. Kim warns that the enduring stalemate will only accelerate North Korea’s development of nuclear and missile technology. In light of these concerns, Kim urges South Korea and the U.S. to actively foster an atmosphere conducive to negotiations while maintaining military deterrence, with the aim of de-escalating tensions on the Peninsula and embarking on efficient crisis management.

Nuclear negotiations with North Korea show no sign of resumption. Since the breakdown of the U.S.-North Korea working-level talks in Stockholm in early October 2019, there has been no advancement in talks for over four and a half years, complicating efforts to denuclearize the Korean Peninsula. Several factors contribute to this prolonged impasse, including the belief that nuclear negotiations are futile and the “strategic patience” policy, both of which stem from the assessment that all past negotiations have completely failed. The former posits that North Korea uses nuclear talks as a mere diversion to gain time, believing that denuclearization will only occur under severe sanctions and pressure or through a regime collapse (Lee 2018: 272-273; Moon 2022: 69-72). Strategic patience, a concept from the Obama administration, entails waiting for North Korea to alter its stance while maintaining sanctions, rather than pursuing active negotiations. Given the absence of any clear negotiation strategy beyond sanctions and pressure, the approach of strategic patience 2.0 continues under the Biden administration (Cheong 2021: 174-190; Ward, Seligman, and Berg 2022).

However, a detailed analysis of North Korea’s nuclear and missile test activities during periods of negotiation and stalemate challenges the view that talks have been entirely futile. Instead, it underscores the need to reevaluate the aforementioned theories and policies in light of the differing outcomes observed during and between negotiation periods. This analysis shows that North Korea refrained from conducting nuclear tests and moderated its missile testing during negotiations, whereas it significantly intensified these activities when talks were absent. Therefore, while negotiations have not led to denuclearization, they have had a tangible impact in moderating the pace of North Korea’s nuclear and missile programs. This reevaluation, detailed below, draws on an extensive review beginning with the Six-Party Talks in the 2000s, offering crucial context for evaluating the trends in North Korea’s nuclear and missile activities up to the present.

During the timeline covered in this analysis, the first negotiation phase began with the trilateral talks among North Korea, the U.S., and China on April 23, 2003 extending through to the first phase of the fifth round of the Six-Party Talks on November 11, 2005. The second North Korea nuclear crisis, emerging in 2002, transitioned into a negotiation phase with the DPRK-U.S.-China trilateral meeting on April 23, 2003. This soon evolved into the Six-Party Talks with the inclusion of South Korea, Russia, and Japan. Over the span of more than two years, these talks culminated in a joint statement on September 19, 2005, pledging to denuclearize the Korean Peninsula, establish a peace regime, and normalize relations. However, this accord faced immediate challenges due to sanctions issues involving Banco Delta Asia (BDA). At the first phase of the fifth round of the Six-Party Talks, from November 9 to 11, North Korea stated that the negotiations could not advance until the BDA issue was settled, resulting in a suspension of the talks. During this negotiation phase, North Korea conducted missile tests, including launches of three short-range ballistic missiles (SRBMs) and two cruise missiles.

The deadlock phase of the Six-Party Talks, which began on November 12, 2005, lasted for about a year until October 30, 2006. North Korea’s response to the freezing of its accounts at BDA and the strengthening of sanctions led to its first nuclear test on October 9, 2006. This phase transitioned back to a negotiation phase following an agreement to resume the Six-Party Talks at a trilateral meeting between North Korea, the U.S., and China on October 31, 2006. During the one year when negotiations were halted, North Korea conducted one nuclear test and launched six SRBMs, two medium-range ballistic missiles (MRBMs), and one space launch vehicle.

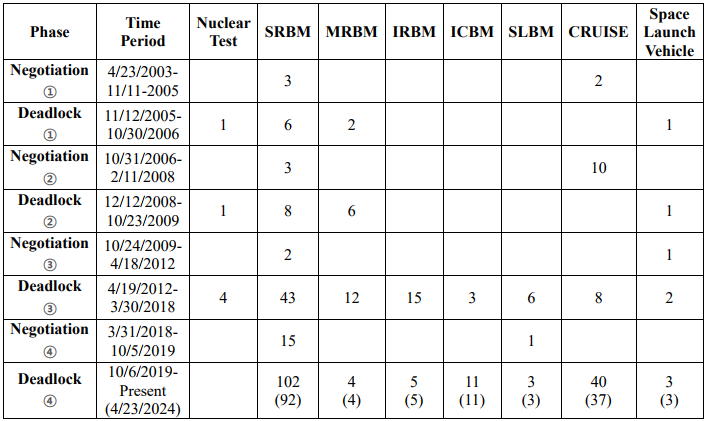

Table 1: Trends in DPRK's Nuclear and Missile Test Activities During Negotiation and Deadlock Phases

* The numbers indicate the frequency of nuclear tests or missile test launches, with data up to April 25, 2023, sourced from the Missile Defense Project at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, and subsequent information based on various media reports.

** The numbers in parentheses in Deadlock Phase 4 indicate the number of missile test launches by North Korea during the Biden administration.

*** Missile classifications are defined as follows: SRBM (Short-range Ballistic Missile) with a range of up to 1,000 km, MRBM (Medium-range Ballistic Missile) with a range of 1,000 to 3,000 km, IRBM (Intermediate-range Ballistic Missile) with a range of 3,000 to 5,500 km, and ICBM (Intercontinental Ballistic Missile) with a range exceeding 5,500 km.

The renewed negotiation phase began on October 31, 2006, and lasted until December 11, 2008. Significant progress was achieved during this period with key agreements reached on February 13 and October 3, 2007, aimed at implementing the “September 19 Joint Statement” from the 2005 Six-Party Talks. Despite these efforts, disagreements regarding verification methods led to the eventual breakdown of the talks in December 11, 2008,, and they have not resumed since. During this two-year negotiation phase, North Korea refrained from nuclear testing but conducted test launches of three SRBMs and ten cruise missiles.

Deadlock persisted from December 12, 2008, to October 23, 2009. During the early days of the Obama administration, North Korea conducted one nuclear test, launched eight SRBMs, six MRBMs, and one space launch vehicle. This phase shifted back to negotiations after the Obama administration signaled openness to bilateral talks, which North Korea preferred. The transition was marked by Ri Kun, the Director General of the North American Affairs Bureau of the DPRK Foreign Ministry, visiting the United States on October 24, 2009, reigniting the negotiation efforts.

The negotiation phase that resumed on October 24, 2009, lasted until April 18, 2012. On December 8, 2009, Stephen Bosworth, the U.S. Special Representative for North Korea Policy, visited Pyongyang with a personal letter from President Obama, which led to progress in discussions. After discussions resumed following delays caused by the ROKS Cheonan sinking and the Yeonpyeong Island shelling in 2010, the parties reached an agreement known as the “Leap Day Deal” in late-February 2012, reaffirming their commitment to the September 19 Joint Statement. The deal included halting North Korea’s nuclear and missile activities, U.S. food aid, people-to-people exchange, etc. However, this agreement collapsed on April 13 due to North Korea’s launch of a space vehicle. Reacting to a UN Security Council condemnation, North Korea declared the dissolution of the DPRK-U.S. agreement on April 18. During this negotiation phase, North Korea tested one space launch vehicle and two SRBMs.

After April 18, negotiations entered a prolonged stalemate that lasted until March 30, 2018, approximately six years later. During this period, the Obama administration continued its policy of strategic patience, applying sanctions and waiting for a shift in North Korea’s stance. During these six years of deadlock, North Korea conducted four nuclear tests and launched 43 SRBMs, 12 MRBMs, 15 IRBMs, 5 ICBMs, 6 submarine-launched ballistic missiles (SLBMs), 8 cruise missiles, and 2 space launch vehicles.

Negotiations resumed on March 31, 2018, with CIA Director Mike Pompeo’s visit to North Korea. This phase continued until the breakdown of working-level talks in Stockholm on October 5, 2019. The dialogue between South and North Korea during the Pyeongchang Winter Olympics facilitated U.S.-North Korea negotiations, leading to the Singapore Joint Declaration on June 12, 2018. This declaration committed to the denuclearization of the Korean Peninsula and the establishment of a peace regime. However, the second U.S.-North Korea summit in late February 2019 concluded without an agreement. This was followed by a summit at Panmunjom in late June, with working-level negotiations ultimately breaking down in Stockholm in October. From 2018 until April 2019, North Korea refrained from missile tests but launched 15 SRBMs and one SLBM from May until October.

Since October 2019, no negotiations have taken place, and as of April 23, 2024, the halt in negotiations has persisted for over four and a half years. During this time, North Korea has not conducted any nuclear tests but has accelerated the development of various missiles, launching 102 SRBMs, 4 MRBMs, 5 IRBMs, 11 ICBMs, 3 SLBMs, 40 cruise missiles, and 3 space launch vehicles. Notably, all but 10 SRBM launches and 3 cruise missile launches have occurred after the Biden administration took office in January 2021.

These observations suggest that North Korea exhibits a markedly different pattern of behavior between negotiation phases and deadlock phases. During negotiation periods, North Korea generally refrains from nuclear tests and often limits its missile testing. In contrast, during deadlock periods when negotiations stall, North Korea carries out nuclear tests and (or) ramps up its missile testing. The absence of nuclear tests and either reduced or halted missile testing during negotiations point to a slowdown in nuclear and missile development, since regular testing is essential for the progression and enhancement of nuclear weapons and missile technology. Thus, the analysis shows that negotiations serve to effectively delay North Korea’s nuclear and missile development, whereas deadlock periods see an escalation in these activities.

These findings effectively challenge the argument that nuclear negotiation are futile, while highlighting the shortcomings of strategic patience. While nuclear negotiations have not led to denuclearization, they are far from being meaningless and have, in fact, contributed to delaying North Korea’s nuclear and missile development. The assessment that nuclear negotiations were merely a tactic for North Korea to buy time is also unfounded. During negotiation phases, North Korea limited its nuclear and missile development activities, and UN Security Council sanctions on North Korea have never been lifted. During the period of strategic patience under the Obama administration through the first year of the Trump administration (Deadlock Phase 3 in Table 1), North Korea significantly advanced its nuclear and missile capabilities, conducting four nuclear tests and aggressively developing a range of missiles, including ICBMs, IRBMs, and SLBMs. Conversely, during the negotiation phase under the Trump administration (Negotiation Phase 4 in Table 1), North Korea upheld a moratorium on nuclear and ICBM tests, limiting missile tests to one SLBM and several SRBMs. With the Biden administration continuing a similar approach to strategic patience, North Korea has intensified its efforts to develop advanced missiles, including hypersonic missiles and solid-fuel ICBMs. In other words, when U.S. adopts strategic patience, North Korea consistently advances its nuclear and missile capabilities.

The prolonged deadlock clearly exacerbates the North Korean issue, contributing to the enhancement of its nuclear and missile capabilities. Although the governments of South Korea and the U.S. assert that they are open to dialogue, they have not shown active willingness to resume negotiations, focusing instead on strengthening military deterrence. While deterrence is necessary, ROK and U.S. must take proactive steps to foster conditions conducive to negotiations. Even if these dialogues do not immediately pave ways to denuclearization, delaying North Korea’s nuclear and missile development could signify the start of effective threat management.

Managing North Korean nuclear threat should aim at reducing and ultimately resolving the threat, and phased arms control presents an effective strategy for this. In this light, comments from Mira Rapp-Hooper, the U.S. NSC Senior Director for East Asia and Oceania, regarding negotiations for "interim steps" and "threat reduction," though lacking specific proposals, are significant as they hint at a pragmatic approach to arms control (CSIS 2024). Phased arms control does not imply toleration of North Korean nuclear weapons, but should rather strive towards denuclearization. However, it is important to avoid setting overly ambitious and unrealistic goals from the start. Instead, efforts should proceed gradually, beginning with threat management and moving towards reduction and then elimination, progressively elevating the objectives. Each step should correspond with appropriate, simultaneous measures. This approach is beneficial as it allows for building mutual trust and sustaining the momentum for negotiation and implementation through incremental actions. Particularly given the intense confrontations and high tensions on the Korean Peninsula, operational arms control that can alleviate tensions, foster a conducive atmosphere for dialogue and negotiations, and effectively manage threats is crucial. The phased implementation of o perational and structural arms control could pave the way for denuclearization of the Korean peninsula. ■

※ Note: This article has been revised, supplemented, and summarized from the author’s recent publication: Kim, Sang Ki. 2023. “The Secondary Effects of Nuclear Negotiations with North Korea: Crisis Management and Delaying Nuclear and Missile Development (in Korean).” Review of North Korean Studies, Vol. 26, No. 3, pp. 199-235.

References

Cheong, Wook-sik. 2021. Peace on the Korean Peninsula, Condition for a New Beginning (in Korean). Seoul: Yurichang.

CSIS. 2024. “Biden Administration’s North Korea Policy: Mira Rapp-Hooper’s Featured Conversation with Victor Cha,” in The JoongAng-CSIS Forum: The Polycrisis in 2024. March 3. https://www.csis.org/analysis/biden-administrations-north-korea-policy (Accessed: April 23, 2024).

Lee, Yong-jun. 2018. Truth and Delusions behind 30 years of North Korean Nuclear Saga: The End of Nuclear Game on the Korean Peninsula (in Korean). Seoul: Hanul Academy.

Missile Defense Project. 2017. “North Korean Missile Launches & Nuclear Tests: 1984-Present.” Missile Threat, Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS). April 20 (Last modified June 1, 2023). https://missilethreat.csis.org/north-korea-missile-launches-1984-present/(Accessed: April 23, 2024).

Moon, Seong-mook. 2022. “North Korea’s Strategic Provocation and ROK’s Countermeasures (in Korean).” Korea Journal of Military Affairs 11: 53-76.

Ward, Alexander, Lara Seligman and Matt Berg, 2022. “Strategic Patience 2.0.” Politico. October 4. https://www.politico.com/newsletters/national-security-daily/2022/10/04/strategic-patience-2-0-00060273 (Accessed: April 23, 2024).

■ Sang Ki KIM is a research fellow at the Korea Institute for National Unification (KINU).

■ Translated and edited by: Jisoo Park, Research Associate

For inquiries: 02 2277 1683 (ext. 208) | jspark@eai.or.kr