The Influence of the COVID-19 Pandemic on the DPRK-China Economic Ties and their Impact on the Korean Peninsula

- Commentary

- October 07, 2022

- Eun-lee JOUNG

- Research Fellow at the Korea Institute for National Unification

In normal economies, currencies weaken in times of difficulty, but something counter-intuitive happens in North Korea. Eun-lee Joung, a research fellow at Korea Institute for National Unification claims that the value of the North Korean won appreciated, and the market prices were remarkably stable although North Korea’s economy suffered its biggest contraction during the pandemic situation. Dr. Joung states that the partial lockdown of the border between North Korea and China, and North Korea’s various changes to deal with the sanctions including the substitution of imported goods with domestic goods may have contributed to the outcome. Meanwhile, she mentions that intensifying U.S.-China strategic competition and the possibility of a prolonged conflict between Russia and Ukraine could increase North Korea’s economic reliance on China and Russia which will impede the re-establishing relations between the two Koreas. However, as the cooperation between North Korea and China in tourism has increased up before the COVID-19 outbreak, Dr. Joung highlights that Pyongyang’s tourism industry is likely to expand, which is expected to stimulate non-governmental exchange and induce North Korea toward openness.

North Korean Economy in the Time of COVID-19

The COVID pandemic has significantly heightened the economic problems facing the North Korean economy as there is a saying that “COVID is the real sanction.” This is a global phenomenon, not limited to North Korea. North Korea responded to COVID-19 through a border blockade, but as a result, North Korea’s trade with China plunged by more than 80%. In general, a decline in trade volume by more than 80% due to external shocks can be critical enough to cause a national financial crisis under normal circumstances. Although North Korea's economy suffered its biggest contraction in the pandemic situation, there has not been a surge in food or energy-related prices yet. In other words, there is at least no significant social unrest regarding the residents’ food, clothing, and shelter. The price of marine products temporarily soared due to the naval blockade. And, the prices of flour, soybean oil, and sugar, which are completely dependent on imports, skyrocketed by 2-3 times during the pandemic. Meanwhile, these imported supplies are used as intermediary goods to make candy and confectionery. Above all, if the North Korean economy is in a crisis, its exchange rates should be rising. Conversely, the exchange rate has decreased, with an appreciation of the North Korean currency (won).

4 Issues Surrounding North Korea-China Trade During the COVID-19 Pandemic

Despite North Korea’s economic difficulties, how could market prices have been remarkably stable? This article attempts to explain the four factors that may have contributed to price stability regarding the trade between North Korea and China. Four issues surrounding North Korea-China trade during the pandemic will be stated below.

First, how long will the border blockade last? In fact, both North Korea and China adopted a flexible border control policy in accordance with their preventive measures against the coronavirus. In particular, there was a strong tendency to move in conjunction with large and small political events within North Korea rather than in China. In other words, the border blockade was conducted at the will of the North Korean authorities, not China, and the border would be opened flexibly if the North Korean authorities take the economic condition seriously. Typically, North Korean market prices began to rise in earnest around January 2021, ahead of the 8th Party Congress in 2021, rather than after the COVID-19 outbreak in February 2021. This is because the North Korean authorities further tightened security on the Sino-Korean border ahead of the 8th Party Congress. Nevertheless, in the long-term trend, North Korea was behaving in compliance with the global trend of acknowledging the difficulty of maintaining a zero-COVID policy, thus trying to gradually open its borders. As an indicator of this trend, the North Korean authorities began to ease the border blockade for ships starting in March 2021. In July and August, they expanded and opened not only national trade between Nampo and Dalian, but also unofficial shipping routes around the Sinuiju-Donggang River, and this tendency has been maintained so far. Meanwhile, rail trade between Dandong and Sinuiju by land was resumed in January this year but has been temporarily suspended due to the spread of Omicron. The trade is expected to resume shortly when the situation improves. In fact, these circumstances are reflected in the prices of imported goods in “Jangmadang“, or North Korea’s unofficial provincial markets.

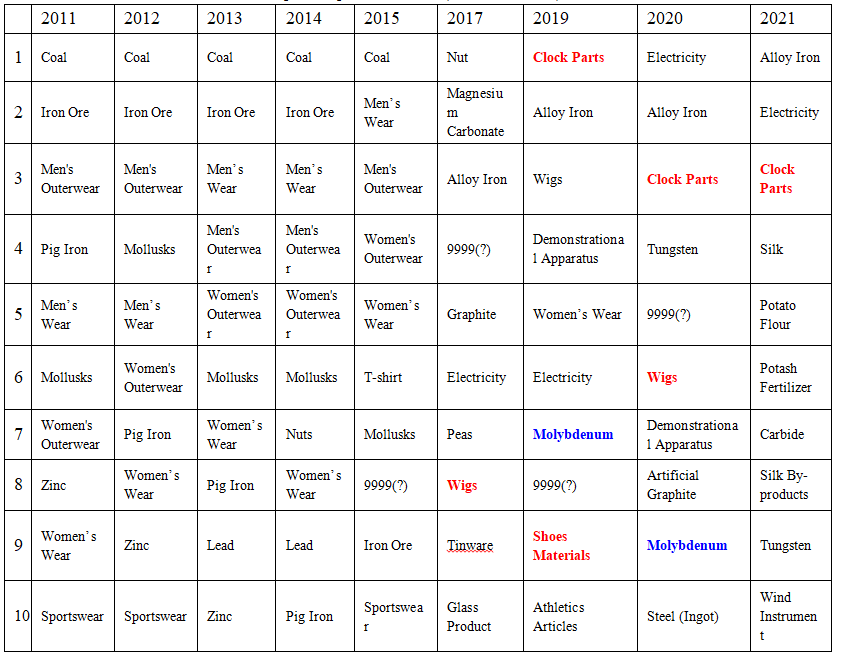

Second, was there any response to economic sanctions due to border restrictions for COVID-19? While the volume of trade between China and North Korea plummeted during this period, there were various changes to deal with the sanctions. Items that do not violate sanctions, such as molybdenum, have emerged as new export items, and North Korea also focused on high-value-added products in the toll processing sector. For example, until the sanctions started to get tightened in 2017, the import of fabrics (used by apparel toll processors) was important in the North Korean economy, being one of the top 10 items to be imported from China. However, when sanctions on toll processing manufacturers tightened in 2018, tobacco and parts of watches became major imports of North Korea from China, and shoes, wigs, parts of a watch, and cigarettes took the lead in North Korea’s top 10 exports. (Refer to , ). These items have higher manufacturing costs than apparel, and thus can be considered high-value-added products.

Third, did the North Korea-China border blockade during the COVID-19 period only have a fatal impact on the North Korean economy? Reversely, blocking imports of manufactured goods can help an economy by increasing the demand for domestically produced goods. Although not significantly highlighted in the official statistics, conducted research reveals that the items recently imported unofficially by ships are mainly raw materials of products “localized” in North Korea. Typical examples were sugar, wheat flour, and soybean oil, which are intermediary goods in food production. In addition, raw materials such as fabric for clothing processing, soap, and detergent were also imported. This can be seen as an attempt to replace imported goods with domestic goods by increasing domestic production.

Fourth, why were there no significant fluctuations in refined oil prices during the COVID-19 pandemic? Is this really because of China? Of course, the reduced refined oil prices can be attributed to a decline in demand for oil due to the COVID-19 recession and a decrease in imported goods. However due to the gradual easing of the blockade on the sea, maritime fishing has been increasing, and the demand for refined oil inevitably arises during the farming season. Moreover, although the logistics industry during the pandemic has shrunk, it is difficult to say that the logistics system is dysfunctional to the extent that it severely restricts transport; the fact that there is no significant difference in product prices between regions supports this claim. In this respect, the possibility of an increased inflow of Russian refined oil cannot be ruled out. Russian wheat, for instance, already had a larger market share than that Chinese wheat as well.

Prospects of Economic Relations between North Korea and China during Post Coronavirus Period and its Implications for inter-Korean relations

It remains uncertain when the COVID-19 pandemic will end, but North Korea seems to be headed in the direction of gradually opening its borders with China. Even though China’s trade with North Korea plummeted, North Korea has also made changes to adapt in response to sanctions. The problem is that sanctions on North Korea have been strengthened to an unprecedented extent since 2016. How would the situation have changed if China and Russia vetoed UN sanctions on North Korea? Perhaps there might be a wider range of economic cooperation between the two Koreas than there is nowadays. In other words, this indicates that even if the COVID-19 pandemic comes to an end, the scope of trade or economic cooperation between North Korea and China will be extremely limited. In particular, the 2019 Hanoi Summit proved that denuclearization and sanctions against North Korea are strongly interlinked. This implies a limit to the extent of North Korea-China economic cooperation as China has participated in tougher sanctions against North Korea since 2016. North Korea and China’s personal exchange-based economic cooperation in the tourism sector, carried out after Kim Jong Un’s visit to China in 2018 and Xi’s visit to North Korea in 2019, is also a by-product of this limitation.

Does this indicate that North Korea-China economic relations cannot be strengthened anymore? The current situation is different from 2016. With the intensification of U.S-China strategic competition, if the current conflict in Ukraine lasts longer, the situation could be favorable to North Korea. In other words, North Korea can strengthen its economic cooperation with China and Russia. In particular, if China and Russia are also subject to U.N. Security Council sanctions, it is questionable whether China and Russia will be able to continue cooperation while maintaining the current framework of sanctions against North Korea. There exists a possibility that China and Russia may even ignore the sanctions and expand the scope of economic cooperation with North Korea. China and Russia’s veto on expanding sanctions against North Korea for its recent provocations support this idea. North Korea can strengthen its economic cooperation with Russia by importing petroleum products and grain such as wheat. The scope of trade with China can be gradually expanded through items that do not officially violate sanctions.

Specifically, cooperation in tourism is likely to expand, as it has increased up until the COVID-19 outbreak. Above all, after Kim Jong-un's visit to North Korea in 2018, the scope of North Korea-China tourism has gone beyond the existing border between the two countries: North Korea will be receiving tourists throughout China. Furthermore, although special tourism zones such as KumGang International Tourism Bureau and Mubong International Tourism Special Zone in Samjiyon County demand large-scale overseas investment, it is currently at a standstill due to sanctions. Thus the possibility of expanding development in such sectors cannot be ruled out. The escalation of strategic competition between the United States and China can bring closer economic ties between North Korea and China, thus increasing North Korea’s economic reliance on China. Such reliance between the two countries could impede the re-establishing relations between the two Koreas. However, in the long term, growth of tourism can stimulate non-governmental exchange, and induce the North Korea toward openness. Non-governmental agencies of South Korea can participate in North Korea-China tourism, which could lead to multilateral economic cooperation among the three countries. In particular, as the growth of tourism is in the interests of neighboring countries such as South and North Korea, China, and Russia, tourism is a useful field for multilateral cooperation. However, this could only happen with the support of China. ■

■ Eun-lee JOUNGis a research fellow at the Korea Institute for National Unification (KINU). She is currently serving as Visiting Scholar at Korean Peninsula Research Center, Beijing University (PKU). She obtained her M.A. and Ph.D. in the Department of Economics from the University of Tohoku in 2004 and 2007. Before joining KINU, she worked as a senior researcher at the Korea Eximbank. Her thesis includes an Analysis of the Development of the North Korean Real Estate Market and A Study of China's trade with North Korea. She also surveyed the ‘Mobile Phone Money’ from the Perspective of microfinance in North Korea.

■ Typeset by Junghoo Park, Research Associate

For inquiries: 02 2277 1683 (ext. 205) | jhpark@eai.or.kr