Evolution of Europe-North Korea Relations: From Active Engagement to Partial Rupture (2/2)

Commentary | March 25, 2024

Antoine Bondaz

Director of Korea Program, FRS

Antoine Bondaz, Director of the Korea Program on Security and Diplomacy at the Foundation for Strategic Research (FRS), examines the EU’s “critical engagement policy” with North Korea, initiated after the first nuclear crisis in 2006. Despite this policy causing a collapse in bilateral trade, the author underscores that European nations have consciously separated humanitarian aid from political agendas, allowing the EU to maintain an important intermediary role in international negotiations with the North Korean regime. However, Bondaz predicts that the rapid shifts in diplomatic priorities for both the EU and DPRK, influenced by geopolitical dynamics, render future political bilateral exchanges highly unlikely.

While the North Korean nuclear and ballistic missile crisis persists in a deadlock, and the reopening of North Korea sparks renewed discussions regarding the potential role of the European Union and its Member States on the peninsula, it is imperative to delve into the history of cooperation between Europe and the country since its establishment in 1948.

With this objective in mind, we present two concise briefs. The first predominantly delves into the events of the 1990s and early 2000s, a post-Cold War era characterized by North Korea's increased international engagement. The second shifts focus to the period from North Korea's inaugural nuclear test in 2006 through to the onset of the pandemic in 2020.

The European approach of active engagement, as outlined in the first note, underwent significant reevaluation following the nuclear crisis of the early 2000s. Engagement became conditional and underwent substantial reduction. This shift had a profound impact on economic relations between Europe and North Korea, a trend that persists to this day. In the wake of North Korea's inaugural nuclear test in 2006, the European Union and its Member States adopted a strategy known as critical engagement. This approach combined the application of pressure through sanctions aligned with those imposed by the United Nations, along with additional autonomous restrictive measures from the EU. Importantly, channels of communication were maintained throughout this period. The strategy's two primary objectives were the achievement of complete, verifiable, and irreversible denuclearization (CVID), as well as the improvement of human rights conditions in North Korea. Despite the collapse of bilateral trade, it is worth noting that humanitarian aid has continued, with certain states, notably Sweden, playing crucial intermediary roles in international negotiations during the late 2010s.

I. Precipitous Trade Decline Preceding Sanctions

Contrary to prevailing narratives, trade between Europe and North Korea witnessed a sharp decline well before the United Nations Security Council's imposition of sanctions through resolutions 2270 and 2321 in 2016, followed by resolutions 2371, 2375, and 2397 in 2017, which instituted sectoral embargoes. The underlying rationale for these sanctions underwent a substantial transformation, shifting from the traditional non-proliferation focus to one centered on imposing prohibitive economic and financial costs. This new approach sought to target the funding sources for North Korea's nuclear and ballistic programs, with the aim of compelling the country to engage in negotiations.

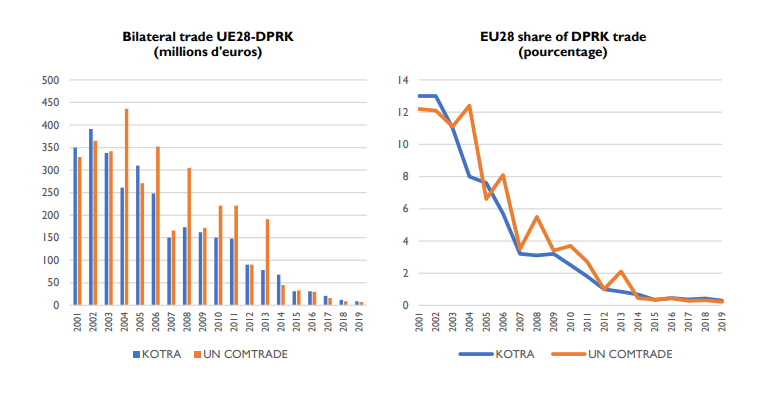

Between 2002 and 2015, trade between EU Member States and the DPRK plummeted from over $350 million to a mere $30 million, constituting a staggering drop of more than 90%. These figures are derived from both the Korea Trade Agency (KOTRA), a South Korean institution, and UN Comtrade, the UN database. Consequently, the European Union's share of North Korea's foreign trade experienced a precipitous decline, plummeting from nearly 13% to a mere 0.3%. From 2016 to 2019, trade continued its downward trajectory, resulting in Europe's share of North Korea's foreign trade, which was already minuscule, diminishing further to 0.2% of the total. Therefore, it is not solely international sanctions that account for this drastic trade decline, although they do now hinder any potential recovery.

In addition to adhering to UN sanctions, the European Union also implemented autonomous measures. Notable among these are the freezing of assets belonging to specific individuals and entities. Furthermore, Council Decision (CFSP) 2017/1860, adopted in October 2017, introduced additional measures including the prohibition of EU investment in North Korea across all sectors, the restriction on the sale of refined petroleum products and crude oil to North Korea, the reduction of the maximum amount for personal fund transfers to the DPRK from €15,000 to €5,000, and the prohibition on the renewal of work permits for DPRK nationals.

In the context of sanctions, it is pertinent to note the positions of various Member States, particularly France, which is sometimes characterized as the European proponent of sanctions against North Korea. Paris maintains a clear stance: adherence to the international legal framework, necessitating strict enforcement of UNSC and EU resolutions, including sanctions. However, despite its reputation for steadfastness, France remains open to the possibility of a partial lifting of sanctions if North Korea takes tangible and verifiable steps towards denuclearization. The debate in Paris revolves around not whether sanctions should be lifted during or after a denuclearization process, but rather, what specific measures the DPRK must undertake before some sanctions can be eased (Bondaz 2020).

It's also crucial to consider North Korean perceptions regarding the potential role of the European Union. Contrary to some portrayals in analyses, the European Union and most of its Member States are not viewed as neutral players. North Korean officials have openly criticized the E3 (France, Germany, and the UK) for their confrontational stance, while conveying more conciliatory signals to other EU member states in Northern and Eastern Europe. Additionally, it's important not to overstate the significance of economic interests (Panda 2019).

The notion of a sudden surge in European investment in North Korea following sanctions relief is misleading (Pacheco Pardo 2019). Even before the implementation of international sanctions, European investment was extremely limited, partly due to the unstable business environment and the potential reputational risks for companies investing in the country. Consequently, not only is a unilateral lifting of European sanctions highly improbable without concrete progress on North Korea's denuclearization, but the scenario of substantial European investment in the country remains unrealistic.

II. European Humanitarian Aid Amidst Proliferation Challenges

Despite the collapse of bilateral trade and escalating tensions driven by North Korea's nuclear and ballistic missile programs, the European Union and its Member States have persisted in delivering humanitarian aid to North Korea. This commitment has endured despite mounting challenges faced by European NGOs in operating within the country. These challenges included Pyongyang's request in 2005 to cease all official and overt aid in response to the European Union's criticism of the human rights situation in the DPRK. Many projects were temporarily halted, resuming only after the relevant non-governmental organizations had restructured and "agreed not to use symbols to identify their sponsors during their work."

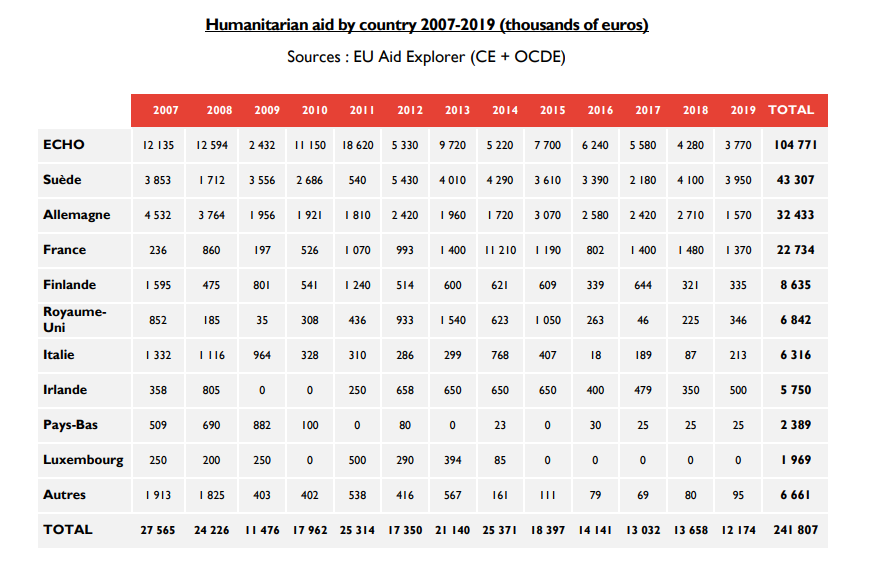

Contrary to assertions of complete disengagement, Europeans have deliberately separated humanitarian concerns from political considerations since the 2000s (Jang and Suh 2017). Prior to the pandemic, the European Union and its Member States consistently provided valuable and essential aid. Between 2007 and 2019, the EU and its Member States contributed €242 million, with a peak of €25 million in 2011. Even from 2016 to 2019, aid remained substantial, surpassing €12 million annually. The contributors' breakdown closely mirrors that of the late 1990s. The European Union, through ECHO, leads with 43% of the total. However, specific Member States play significant roles, including Sweden (18%), Germany (13%), and France (10%). Sweden's role was particularly noteworthy pre-pandemic, with its contribution maintaining exceptionally high levels, accounting for over 30% of the total aid provided to the DPRK in 2018 and 2019.

Similarly, France, often scrutinized for its stringent stance on non-proliferation, emerges as a pivotal partner, contributing to aid efforts for the North Korean population, with a focus on food assistance and support for French NGOs operating in the country. Additionally, France supports the World Food Programme and UNICEF, lending credibility to the pivotal role played by the French Cooperation Office established in Pyongyang in 2011.

The European Union's aid initiatives are dedicated to supporting tangible projects and addressing emergency situations. In 2019, in response to a seasonal drought, the EU allocated €55,000 to assist the International Federation of the Red Cross in providing crucial aid to the most vulnerable families in South Hamgyong Province, which was severely affected. Similarly, in August 2018, when North and South Hwanghae provinces faced extensive flooding and landslides, the European Union committed €100,000 to aid those hardest hit by the disaster. Additionally, in 2016, the EU contributed €300,000 to supply essential items to families affected by devastating floods in North Hamgyong, the northernmost province. Another €300,000 was allocated for an initiative led by the Finnish Red Cross (FRC) aimed at enhancing the resilience of rural communities to future floods and droughts, both at the local and national levels.

III. European NGOs, a Concrete Example

European non-governmental organizations (NGOs) operate on the ground, maintaining close proximity to the local communities. They have established enduring and dependable relationships with North Korea, surpassing the tenure of American and South Korean NGOs. Among the NGOs that were present in North Korea before the pandemic forced their withdrawal, all four were of European origin. These organizations included Première Urgence Internationale, Triangle Génération Humanitaire, Concern Worldwide, and Welthungerhilfe, alongside the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies and six United Nations agencies. Handicap International and Save the Children had withdrawn from the country in 2019.

Additionally, EU Member States ensured that NGOs received exemptions from the UN Security Council Resolution 1718 Committee, enabling them to continue their vital humanitarian work in the country. Notably, in 2019 and 2020, NGOs and companies from Finland (Finn Church Aid), France (Triangle Génération Humanitaire, Première Urgence Internationale, and Médecins Sans Frontières), Germany (Deutsche Welthungerhilfe), Ireland (Concern Worldwide), Italy (Agriconsulting SA and Agrotech SPA), and Switzerland (Swiss Humanitarian Aid) were all granted exemptions.

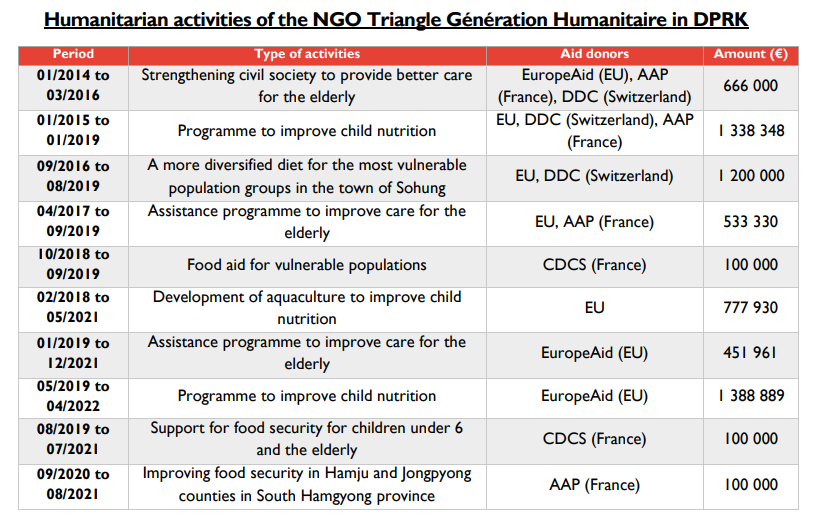

An intriguing aspect is the extensive range of humanitarian projects undertaken by the French NGO Triangle Génération Humanitaire between 2002 and 2020 in North Korea. Firstly, these endeavors received funding from a multitude of international contributors, predominantly of European origin, including the EU's Directorate-General for Civil Protection and Humanitarian Aid Operations (ECHO) and EuropeAid, the Programmed Food Aid (PFA), and the Crisis and Support Centre (CDCS) of the Ministry of Europe and Foreign Affairs, the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (SIDA), and the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation (SDC). Secondly, the financial commitment was substantial, amounting to nearly €20 million over a span of two decades. Thirdly, the projects encompassed a wide array of areas, ranging from agricultural development and food security to the rehabilitation of drinking water systems, and the enhancement of sanitary infrastructures. This also included the distribution of food aid in children's institutions, improving living conditions in retirement homes, and supporting associations advocating for the rights of the elderly, among others.

The table below presents the ten most recent projects executed by the NGO between 2014 and 2019. Unfortunately, most of these initiatives had to be temporarily suspended due to the pandemic and the departure of foreign aid workers in the spring of 2020."

IV. What Role will Europe Play in the Future?

The pandemic-induced closure of North Korea in 2020 has further deepened the rupture between Europe and the country. Bilateral trade has effectively dwindled to zero, hampered by the absence of UN Comtrade data due to North Korean non-reporting. The four European NGOs that previously operated in the country have withdrawn, and European humanitarian aid has sharply declined, plummeting from €8.69 million in 2020 to less than €400,000 in 2022, according to European Commission figures. The departure of all European diplomats from North Korea has led to a collapse in both official and unofficial interactions, including in Europe.

This situation prompts crucial questions about the potential for future exchanges, particularly on the political front, between Europeans and North Koreans. This includes considerations of reopening embassies in Pyongyang and reshuffling the teams of North Korean diplomats stationed in Europe, many of whom have spent extended periods abroad— all of them for at least four years.

One significant risk lies in the potential difficulty of integrating the new diplomatic teams, combined with a waning political appetite for constructive dialogue with North Korea. This is exacerbated by the proliferation of diplomatic priorities in Europe's periphery and the Indo-Pacific region, which have relegated North Korea to a marginal position on the European agenda.

A second risk stems from the possibility of North Korea prioritizing the revitalization of relationships with partner countries, ranging from China and Russia to select nations in South-East Asia, the Middle East, and Africa. This could signify a form of diplomatic disengagement.

A third risk is the potential loss of credibility, as well as influence, for certain Member States that have historically played pivotal roles as intermediaries and facilitators. This was evident in the 1990s for Germany and in the 2010s for Sweden. The polarization of international relations, shifts in political majorities in Stockholm, and, most importantly, Washington's unclear stance on engaging in negotiations with Pyongyang could lead to the weakening of one of the few leverage points available to Europeans.

※ This article was co-published by the FRS and Global NK.

References

Bondaz, Anotine. 2020. “Strictly Enforcing Sanctions Without Closing the Door: France’s Position on International Sanctions against the DPRK.” Institute of Korean Studies, Freie Universitat Berlin. Briefing 4.

Jang, Suyoun, and Jae-Jung Suh. 2017. “Development and Security in International Aid to North Korea: Commonalities and Differences among the European Union, the United States and South Korea.” The Pacific Review 30, 5: 729-749. https://doi.org/10.1080/09512748.2017.1294614

Pacheco Pardo, Ramon. 2019. “Europe Has a Lot to Offer on the Korean Peninsula.” Global Asia 14, 2: 114-119. https://www.globalasia.org/v14no2/focus/europe-has-a-lot-to-offer-on-the-korean-peninsula_ramon-pacheco-pardo

Panda, Ankit. 2019. “What Can the EU Contribute to Peace on the Korean Peninsula?” The Diplomat. July 22. https://thediplomat.com/2019/07/what-can-the-eu-contribute-to-peace-on-the-korean-peninsula/

■ Antoine Bondaz is the Director of the Korea Program on Security and Diplomacy at the Paris-based Foundation for Strategic Research (FRS).

■ Typeset by: Jisoo Park, Research Associate

For inquiries: 02 2277 1683 (ext. 208) | jspark@eai.or.kr

Security and External Relations

Deciphering North Korea’s Policy Shift: Annihilation of ROK vs. End of Kim Regime

Young-Sun HA | 11.March.2024

Evolution of Europe-North Korea Relations- From Active Engagement to Partial Rupture (1/2)

Antoine Bondaz | 26.February.2024

Crisis Management Strategies for a Potential Conventional Escalation on the Korean Peninsula

Ho-ryung Lee | 12.December.2023

LIST