Capacity Building and Development Cooperation for North Korea

Special Report | July 19, 2022

Changyong Choi

Associate Professor at the Seoul National University Graduate School of Public Administration (GSPA)

In this Special Report, Changyong Choi, Associate Professor at the Seoul National University Graduate School of Public Administration, calls for South Korea to engage in trilateral cooperation with international financial institutions to offer capacity-building programs and knowledge-sharing projects to North Korea, thereby providing the North with education and training on the market economy. The author argues that it is important to encourage the North to divert investment from nuclear development to technological and capital development, legalize commerce, and formalize institutions for taxation and trade regulations. He further states such technical development will help to build state capacity, reduce inter-Korean tensions, and support North Korea’s transition to a market-based economy.

Technical cooperation—a key means of international development cooperation—has the potential to bolster North Korea’s state capacity and contribute to establishing a solid foundation for political institutions. Prior to resolving the North Korean nuclear issue, the newly elected Yoon Suk-yeol administration should use capacity-building programs as a policy tool to reduce inter-Korean tensions. Establishing a trilateral cooperation mechanism with the international community to open a channel of communication between the two Koreas and providing education and training programs that genuinely benefit North Korea will contribute to North Korea’s transition to a market economy.

The Need for Strengthened North Korean State Capacity to Support Development Cooperation

In the 1970s, North Korea firmly adhered to a state-centered socialist planned economy. Since then, the country has attempted to study capitalist economies through its own educational institutions. In 1998, the Najin Enterprise School was established to provide education on market economies. In the 2000s, the school began to emphasize information service, modern corporate management, and managerial skills in order to increase the managerial efficiency and autonomy of North Korean businesses. Although this has brought forth limited change in North Korea, this contrasts with cases exhibited in other former socialist countries like the Soviet Union and East Germany, where economic and political officials could not introduce citizens to the principles of a market economy until the country officially introduced reform and openness initiatives or underwent a formal change of regime. Countries pursuing state-led development strategies—known as the “Developmental State” model—achieved rapid economic development in a relatively short period of time by undertaking national efforts to develop human capital while focusing on bureaucratic capacity as a major engine of economic development. Former socialist countries also recognized that high quality human resources—namely, “cadres”—play an essential role in successfully transitioning to a market economy. Accordingly, North Korea has also begun to emphasize educating bureaucrats and core economic bureaucrats about the “market economy.”

Difficulties in Pursuing Capacity-building Cooperation with North Korea

In order to effectively pursue technical cooperation and knowledge-sharing projects, it is necessary, above all, to have an in-depth understanding of the country and its society. This is because systems and policies that have worked successfully in certain countries cannot be applied to other countries with different historical, social, political, and economic circumstances. As such, it is important to start by exploring the implications of recent changes within North Korea, especially “marketization from the bottom,” and tracking the political and economic evolution of tension and compromise within state-society relations surrounding the “market.”

A key issue when pursuing knowledge-sharing projects on the market economy with North Korea lies in the fact that while North Korean authorities actively participate in educational programs proposed by the international community, they filter out some of the contents and tend to quit mid process. Such selectivity stems from the fact that North Korea’s primary interests are attracting capital while ensuring that international technical cooperation projects do not threaten the existing system. This limits information North Korea consumes to only fragmentary knowledge and skills necessary for economic maintenance.

Furthermore, the execution of capacity-building programs and technology cooperation projects also exposes the inconsistency and instability of holding such projects. This is mainly due to recent political changes. Projects lacked continuity and regularity; coordination between projects was tenuous. In addition, though knowledge-sharing projects were requested by a single entity—North Korea—a diverse set of suppliers were responsible for carrying them out, and the mechanisms for cooperation and coordination between these suppliers were weak. This demonstrates that, in order to improve local governance and promote synergy between future projects, it is necessary for participating institutions to align their values, goals, and business principles.

Recent Changes in North Korea and the Spread of the Market Economy

Recently, although the market economy has shrunk considerably due to COVID-19, remarkable changes have continued to occur within North Korea. As mentioned earlier, “marketization from below,” that is, growth of the informal economy, has continued since the “Arduous March” in the mid-1990s. Notwithstanding crackdown by authorities, the market economy and private economy are predicted to grow even further. Information sharing, movement, and exchange between North Korea and the outside world via market activities are increasing; these bottom-up, self-sustaining trends serve as clues to help predict subtle societal changes in North Korea. To be sure, these changes do not necessarily indicate that North Korea has committed to reform and openness, but it is still necessary to pursue technical cooperation and knowledge-sharing programs to prepare for and minimize the future cost of unification and North Korea’s economic integration. After the fruitless conclusion of the U.S.-DPRK and inter-Korean summits, international North Korean cooperation programs have also come to a virtual standstill. Therefore, the Yoon administration’s objective is to strengthen the South’s security posture against the North while at the same time determining when, how, and under what conditions to restore economic cooperation between the two nations. Proactively resolving the nuclear issue could encourage inter-Korean economic cooperation and stimulate North Korea’s economic growth. Such inter-Korean integration would be able to minimize the social and economic costs unification would be minimized.

Proposals for Capacity Enhancement Programs in North Korea

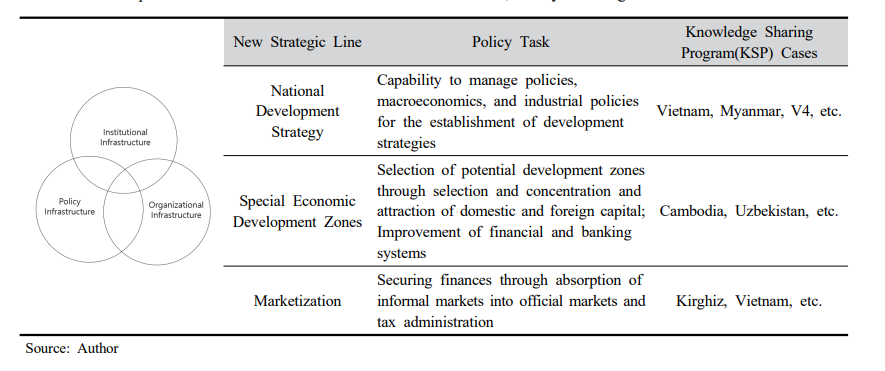

Examples of potential specific capacity-building programs are as follows. First, programs should offer case-oriented education to strengthen public policy planning and enforcement capabilities; statistics training for professionals to better operate and manage the national statistical system; and education on budget and finance, market economies, and corporate activities. Second, as part of the transition from a planned economy to a market economy, said programs should promote private economic activity through measures such as legalizing retail commerce and expanding the autonomy of state owned enterprises (SOEs). Third, programs should work to incorporate consumer products traded on the black market into the official market, expand taxation mechanisms to normalize the provision and pricing of utilities, establish order in goods distribution by instituting a reporting and permission system for commercial transactions, and stabilize national finances. Once a foundation for early and medium-term development cooperation is established, a stable monitoring and evaluation system can be built to support medium to long-term national development strategies, fine-tune development support initiatives, and enhance the efficacy of development cooperation.

Examples of established institutional, policy, and organizational infrastructure in North Korea

In addition, it is necessary to not only systematically review projects being carried out in cooperation, but also share policy suggestions for bilateral projects between the two Koreas with participating international financial institutions. More specifically, when a country in transition receives technological and financial support from international financial institutions, it may also face pressures for governance reform, such as increasing transparency, improving reliability, and ensuring citizen participation in the policymaking process. As compliance to such “conditionalities” will be a very sensitive undertaking for North Korean authorities, technical support programs should be able to accommodate and enhance their understanding of such conditions. It is particularly important to review technical cooperation projects with international financial institutions, given that these institutions are able to provide capital necessary for large-scale transitions. According to the criteria used to classify countries in transition, North Korea is a low-income country with poor governance; this should be considered when devising strategies for economic cooperation.

In addition, North Korea should seek incentives to divert the technology and capital currently being used to develop nuclear weapons and missiles towards a more productive industrial sector. In order for the two Koreas to operate in the future as partners with complementary economies, it will first be necessary for North Korea to overcome its current rigid, ideology-based view and analyze its economic level and development stage more objectively. Even if tensions regarding North Korea’s denuclearization persist, efforts to establish economic cooperation—or even peace—with North Korea should continue. Short-term cooperative policy and institutional infrastructure projects should come before large-scale economic cooperation initiatives. From this point of view, it is also urgent to establish a channel for policy dialogue with Pyongyang in order to share the achievements and know-hows on execution accrued by the South Korean government and other related organizations.■

■ Changyong Choi is Associate Professor at the Seoul National University Graduate School of Public Administration (GSPA). His research areas are governance reform, digital democracy, international development cooperation, and the North Korean economy. Professor Choi graduated from Korea University with a bachelor’s degree in sociology and earned his master’s degrees in public policy and applied economics (MPP and MAE) from the University of Michigan. He received his Ph.D. from Syracuse University’s Maxwell School of Citizenship and Public Affairs with his doctoral dissertation, “Political and Institutional Origins of Market Development in North Korea: Focusing on State-Society Relations.”

■ Typeset by Seung Yeon Lee, Research Associate; Sarah MacHarg, Intern

For inquiries: 02 2277 1683 (ext. 205) | sleeeai.or.kr

Inter-Korean Relations and Unification

President Yoon's Trip to Madrid: Rethinking Seoul's Policies toward Moscow, Beijing, Tokyo, and Pyongyang

Yang Gyu Kim | July 11, 2022

The Yoon-Biden Summit and Prospects for the Yoon Administration’s North Korea Policy

Young-ho Park | June 21, 2022

Prospects for DPRK-China Relations in 2022 and Challenges for the Yoon Administration

Bong Sup Shin | June 08, 2022

LIST